Amanda Williams on her first international exhibition

15.9.21

PHOTO 2021 artist Amanda Williams features in a group exhibition at Open Eye Gallery in Liverpool alongside fellow PHOTO 2021 alum Atong Atem and James Tylor. The exhibition Whose Land Is It? explores ideas of the landscape and the elements of it which may have previously escaped our attention. We caught up with Amanda from her home in Sydney to talk through her first international exhibition and her how her research driven approach informs the final pieces.

Hi Amanda, congratulations on your first international exhibition. Why was it important for you to participate in this exhibition? And what does it mean for your practice to exhibit abroad?

Thank you. It was an incredible opportunity to work with curator Mariama Attah. From the outset she offered an open, collaborative exchange of ideas and as making new work for the exhibition and the personal experience felt significant. Such generous conversations with curators are valuable and rare; offering a space for the creation of new work in the short term is in itself incredible, however in the long term, they offer exciting new pathways for insight and the potential for new techniques and ideas to evolve. It was particularly rewarding to be able to show this work in the UK – the level of exposure for my practice, the ability to share uniquely Australian stories with a UK audience was amazing. I’m so grateful!

Aton Atem, Monstera Obliqua & Photo Weavings 2021 (2021). Installation view Whose Land Is It?, Open Eye Gallery, Liverpool

James Tylor, Economics of Water (2018). Installation view Whose Land Is It?, Open Eye Gallery, Liverpool

On the back of your PHOTO 2021 commission The Alpine Moth, you are now exhibiting in the UK at Liverpool’s Open Eye Gallery alongside other PHOTO 2021 artists Atong Atem and James Tylor in a show titled Whose Land Is It? Can you tell us about the work that you are presenting in that show?

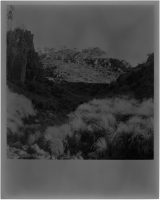

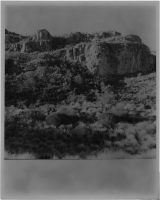

As with previous work, this new series of photographs is research driven, developing from a number of thematic threads: looking into the history of early Australian Photography and photographers, specifically landscape photography. The work also operates as a direct response to feminist approaches to cultural production, politics, and society. Titled, Nichols Gorge Walking Track, Kosciuszko National Park, 2021, the work documents a walk I completed and photographed in 2018. Using expired film and printing the negatives on fogged vintage silver gelatin paper, I was interested in the trace of light and passage of time that might become visible in the final works. By using vintage/expired photographic materials (film, paper, chemistry), I am hoping to expose present and past historical contexts within the same ‘frame’, highlighting the afterlife of photography in our present, contemporary context. In addition to the material experimentation – thematically, I was also interested in the symbolism of the mountain and the cave in European modernist and Romantic discourse and how this relates to the contemporary conversation around ‘landscape’ in Australia.

TO SEE A VIRTUAL TOUR OF WHOSE LAND IS IT? CLICK HERE

Amanda Williams, Nichols Gorge Walking Track, Kosciuszko National Park (2021). Installation view Whose Land Is It?, Open Eye Gallery, Liverpool

This series focuses on landscape from a feminist perspective. Can you tell us more about your approach to exploring these themes?

I have long been interested in the history of environmental movement of the 1970s and the influence that had on the feminist art practices of that time – specifically female artists working with photography. Simply put, I am interested in interrogating histories of female representation in the cultural traditions of ‘landscape’ and secondly the place of women in the history of photography. In this particular work, I was thinking about and researching the way landscape, in the Australian imagination, was critically and artistically explored in the mid to late 19th century in Australia. I frequently return to a book called Women and the Bush: Forces of Desire in the Australian Cultural Tradition by Kay Schaffer, from 1989. Here Schaffer points to the culture of masculinity that historically permeated all aspects of Australian society especially the ‘bush’, as a space where women were marginalised even invisible in many ways. The bush was portrayed as a man’s place in early colonial literature and particularly in artwork of the 19th century, yet ironically the landscape itself was discussed and characterised as feminine and something ‘wild’ that needed to be tamed.

A key aspect of this work and my practice generally, is my interest in what the photographic image could be seen to ‘do’, how it performs, what it represents and what it can become over time. I choose my own view – a complicated view at times, navigating complex frames of reference and questioning representation. I also like to think of the photograph as an event itself, something active, a performance; not simply the witness to and objective recorder of ‘key’ events. This conceptual encounter with history, memory and time, could be seen to mirror our relationship with life, history the photograph itself. In this sense, the work complicates and obscures the ‘view’ yet also contains the potential to unravel and clarify our engagement with and perception of landscape over time. The photograph is in this way, a distinctly unfixed and variable event. I love the adjective Isobel Parker Philip (Curator Australian Art at AGNSW) applies to photography, calling it a ‘slippery’ medium.

Amanda Williams, Nichols Gorge Walking Track, Kosciuszko National Park (2021)

Amanda Williams, Nichols Gorge Walking Track, Kosciuszko National Park (2021)

Can you tell us more about the site that inspired this work?

This series captures my physical encounter with a particular site that I have visited numerous times, the Nichols Gorge Walking Track in the high plains area of Kosciuszko National Park. The National Park was formally established in 1967, covers 6,900-square-kilometrs and includes Australia’s highest mountain peak, Mt Kosciuszko. The grade 4 track I walked is approximately 7km long, a 4–6-hour loop, that follows a dry creek bed, taking you deep into the gorge, passing 3 limestone karst caves and opening out onto the high, broad, grassy and rocky plains. It is a place literally stepped in history where the geological timeline can be clearly ‘read’ in the strata of the rock formations.

Part of my interest in photographing landscape includes being immersed in the space not simply passing through. In this way, I develop research that covers the history of the site, connecting with local First Nations community and Aboriginal Land Council where possible, National Parks rangers and in the case of this work, geologists working to develop broader understanding of Karst landscapes, conservation, and protection practices.

My photographs represent many hours of engagement off site before I even take a photograph. Following the research, I often return to the site multiple times, recording the walks with various cameras, under different conditions.

Amanda Williams, Nichols Gorge Walking Track, Kosciuszko National Park (2021). Work in progress.

This work, like many of your works, use analogue processes, can you step us though the steps and methods that you used here?

The photographs in this series were taken on my 1957 Yashica-Mat Twin Lens Reflex camera back in 2018. The negatives and prints remained in my ‘archive’ until conversations for this exhibition began with Mariama late 2020. The photographs document my walk, covering the entire length of the gorge and the return, 6 hours or so, with this camera in hand. I printed the medium format 6×6 negatives on expired photographic paper at the time (vintage Agfa Brovira Speed RC, 8x10inch circa 1980’s). Due to the age of the paper, severe fogging was present in the final photographic prints. Fogging is the slow incidental exposure of the paper over time – this fogging can occur despite the boxes of paper being ‘new’ old stock and never having been opened. I love the idea that light has penetrated a dark, enclosed space, slowly over time. Like light reaching into the depths of a cave via a narrow opening. This fits with my interest in the materiality of photography and its history. I am excited by the thought that the invention of photography wasn’t the exclusive expression of a 19th century scientific mind. Rather, the proposition that the idea of photography, the perception and use of the ‘technology’ and what it is capable of philosophically and socially, is as old as the caves themselves.

Theresa Mikuriya in her 2016 publication, A History of Light: The Idea of Photography, makes this connection between caves and photography when she writes, ‘the inundation of light into the cave resonates very well with certain technical aspects of photography’. It is noted on the back cover of the book, “If we depart from the technologically oriented accounts and consider photography as a philosophical discourse, an alternative history appears, one which examines the human impulse to reconstruct the photographic or ‘the evoking of light”.

I am also reminded of one of my favourite films by Werner Herzog Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010); In his voice over narration he seems to suggest that the charcoal cave drawings might just be the first representation of the world captured as movement, like cinema itself, hand drawn on the walls of the cave, multiple renderings of the bison outside the cave, drawings repeated one over the other … perhaps tracing the shadows that were dancing across the walls of the cave. A true ‘pencil of nature’ to take Henry Fox Talbots phrase.

Anyway, back to the work for the exhibition… I scanned the original 8×10 silver gelatin photographs, sent the digital files across to the UK to be printed, enlarged them to mural scale via lambda C-Type printing processes. This analogue to digital to analogue translation, across continents, felt appropriate for this body of work. The resulting prints are approx. 140cm by 110cm, hung in a single horizon line around the gallery wall. To add to the cave like atmosphere, the walls of the gallery are painted a deep, dark green with the spot lit photographs hanging unframed, appearing a little like silvery shadows in this dark space. The green was Mariama’s idea – I might just have to repeat this again in future installations – I really love those green walls!

Finally, can you suggest any further reading if people are interested in exploring these ideas further?

Dark Emu by Bruce Pascoe

Women and the Bush: Forces of Desire in the Australian Cultural Tradition by Kay Schaffer

A History of Light: The Idea of Photography by Theresa Mikuriya

The Miracle of Analogy: Or The History of Photography, Part 1 by Kaja Silverman

Failed Images: Photography and its counter practices by Ernst van Alphen

Singular Images Failed Copies: William Henry Fox Talbot and the Early Photograph by Vared Maimon