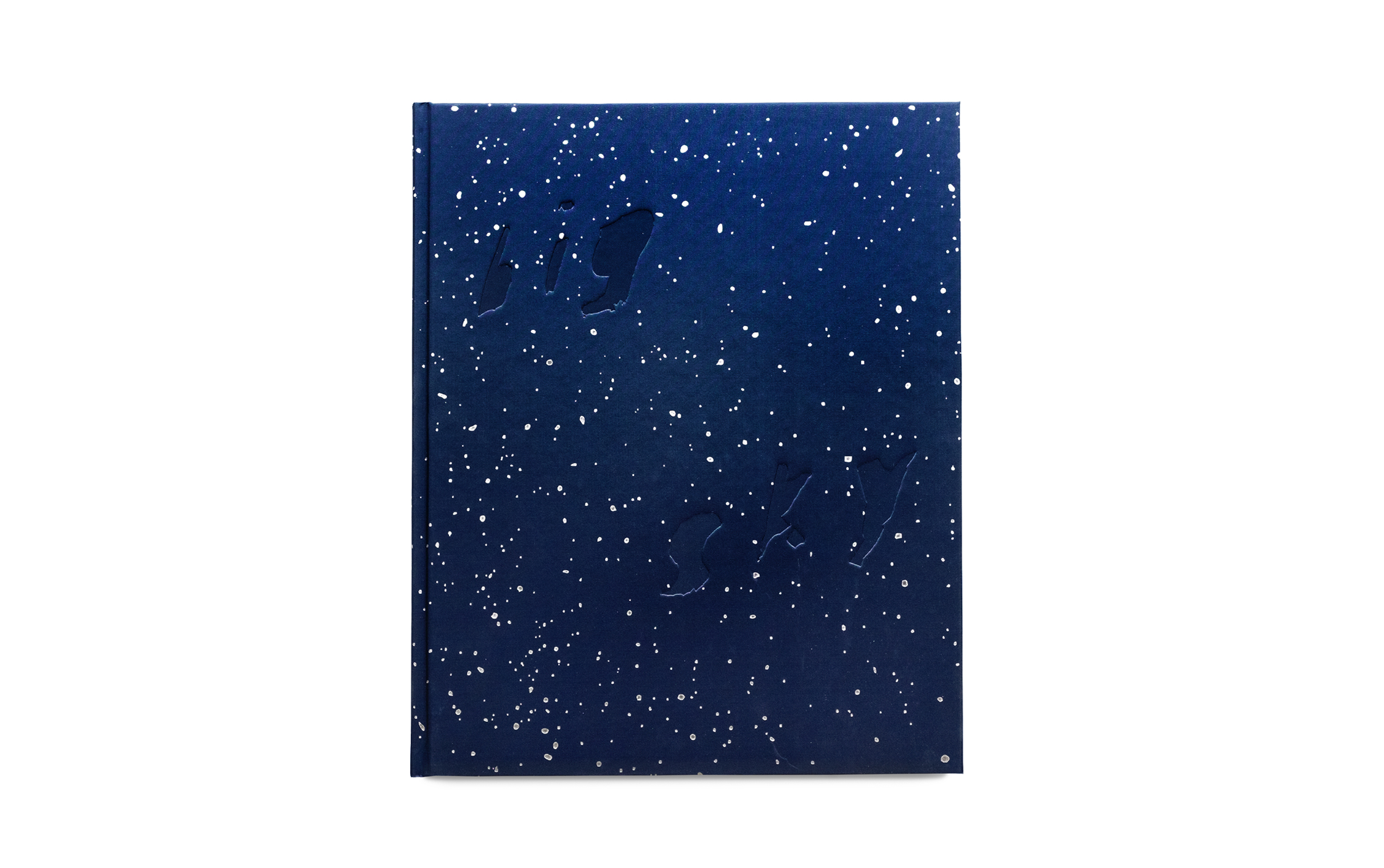

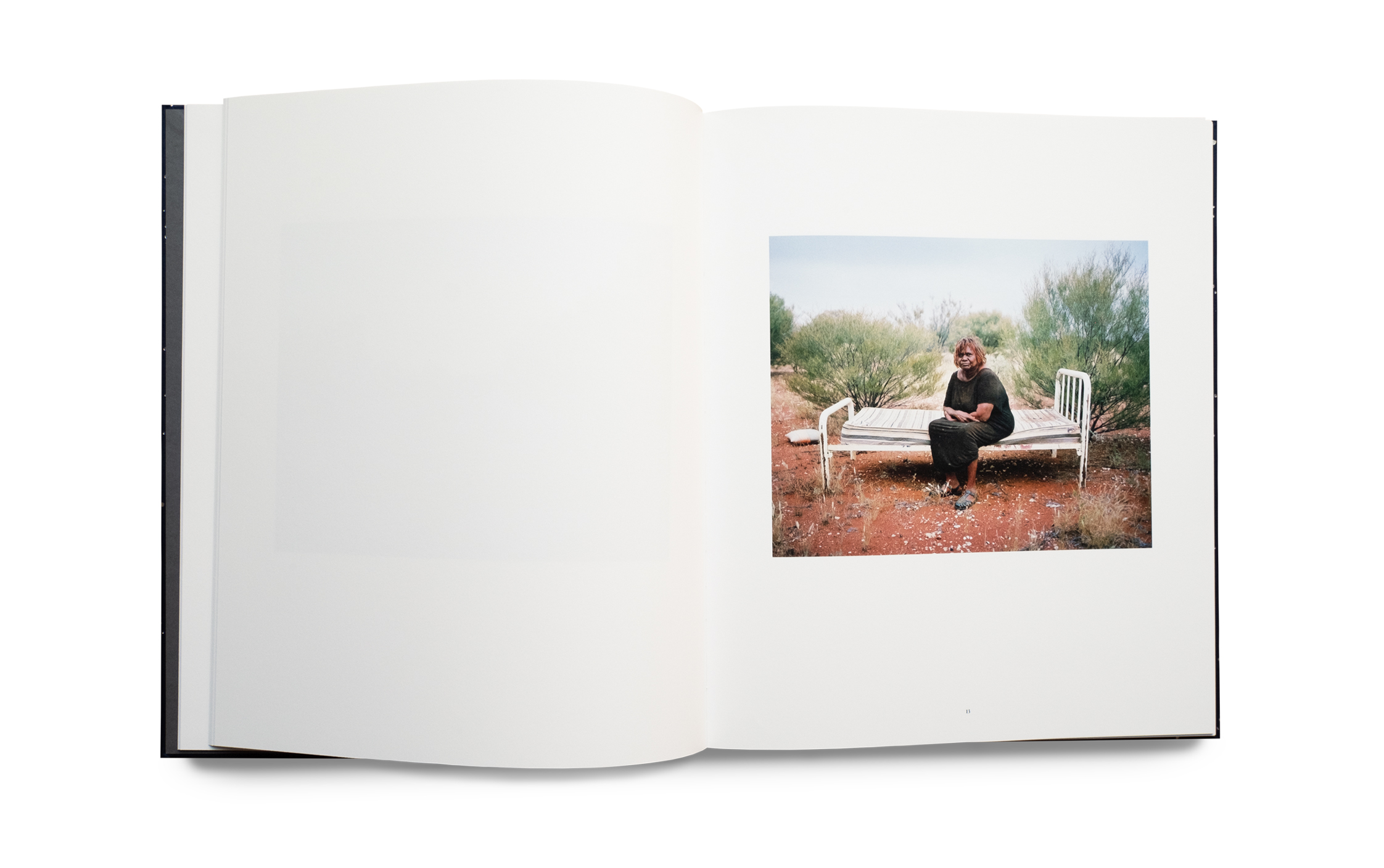

Image: Adam Ferguson, from the series Big Sky, 2023.

PHOTO Book Club – Adam Ferguson on Big Sky

15.10.24

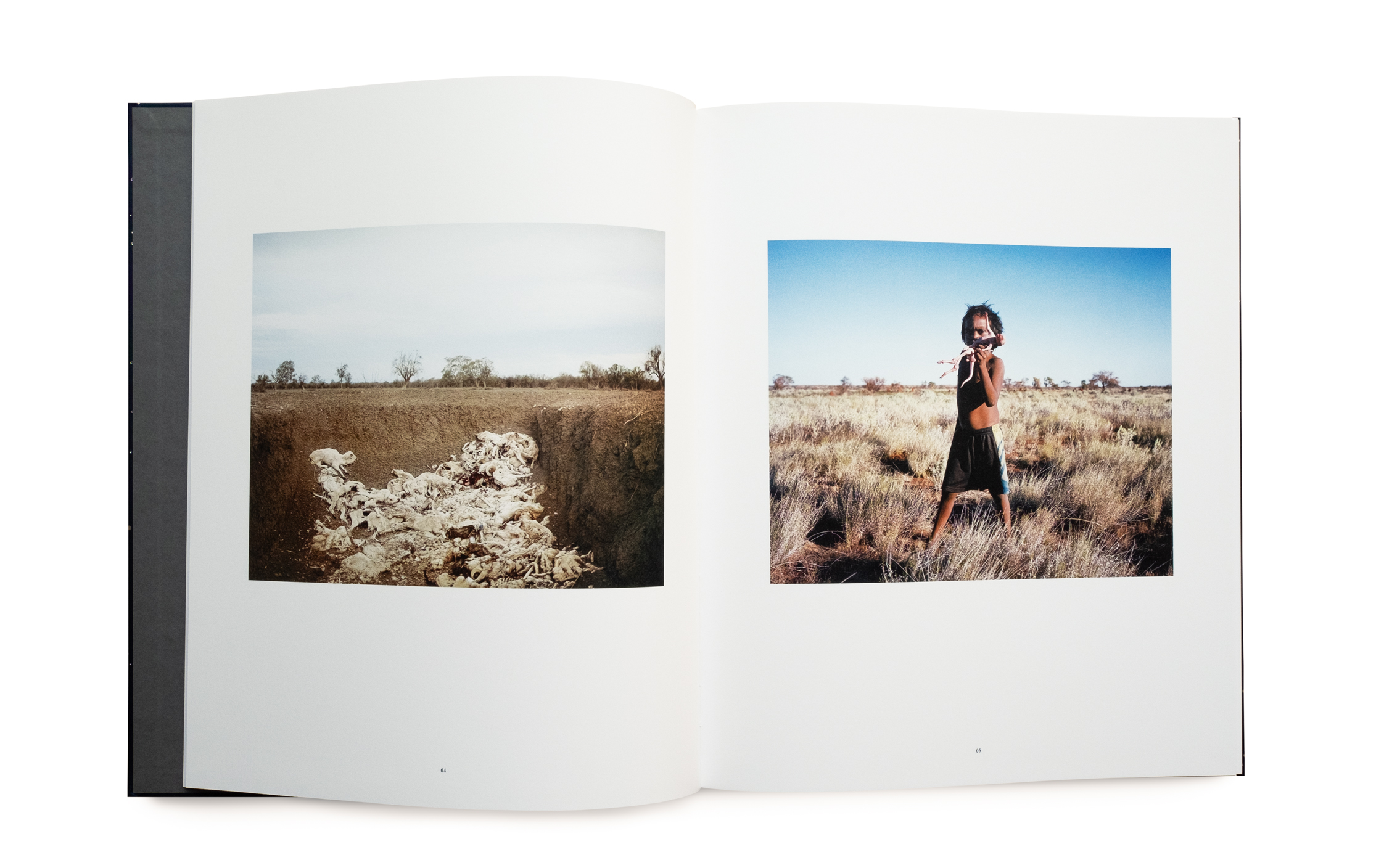

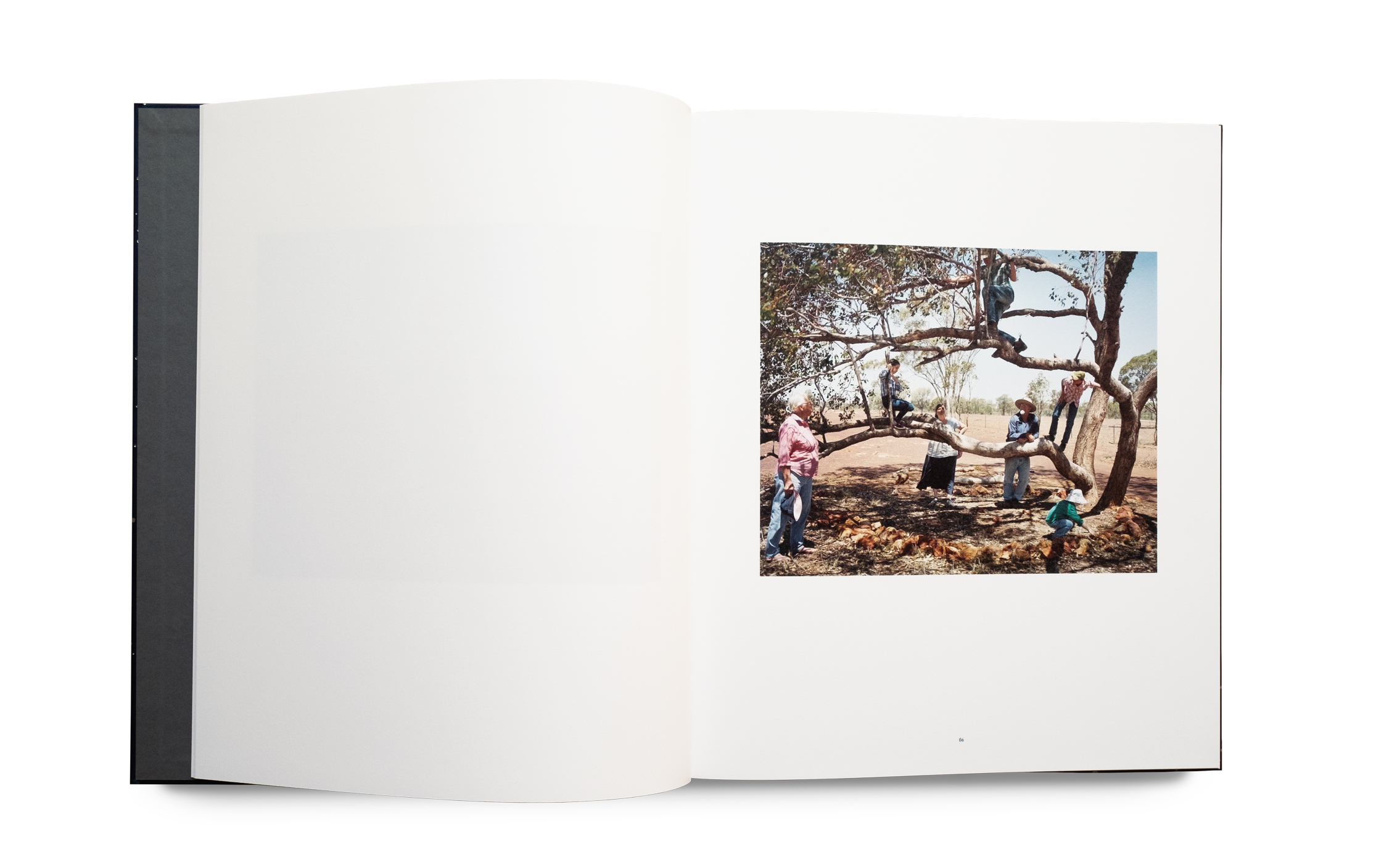

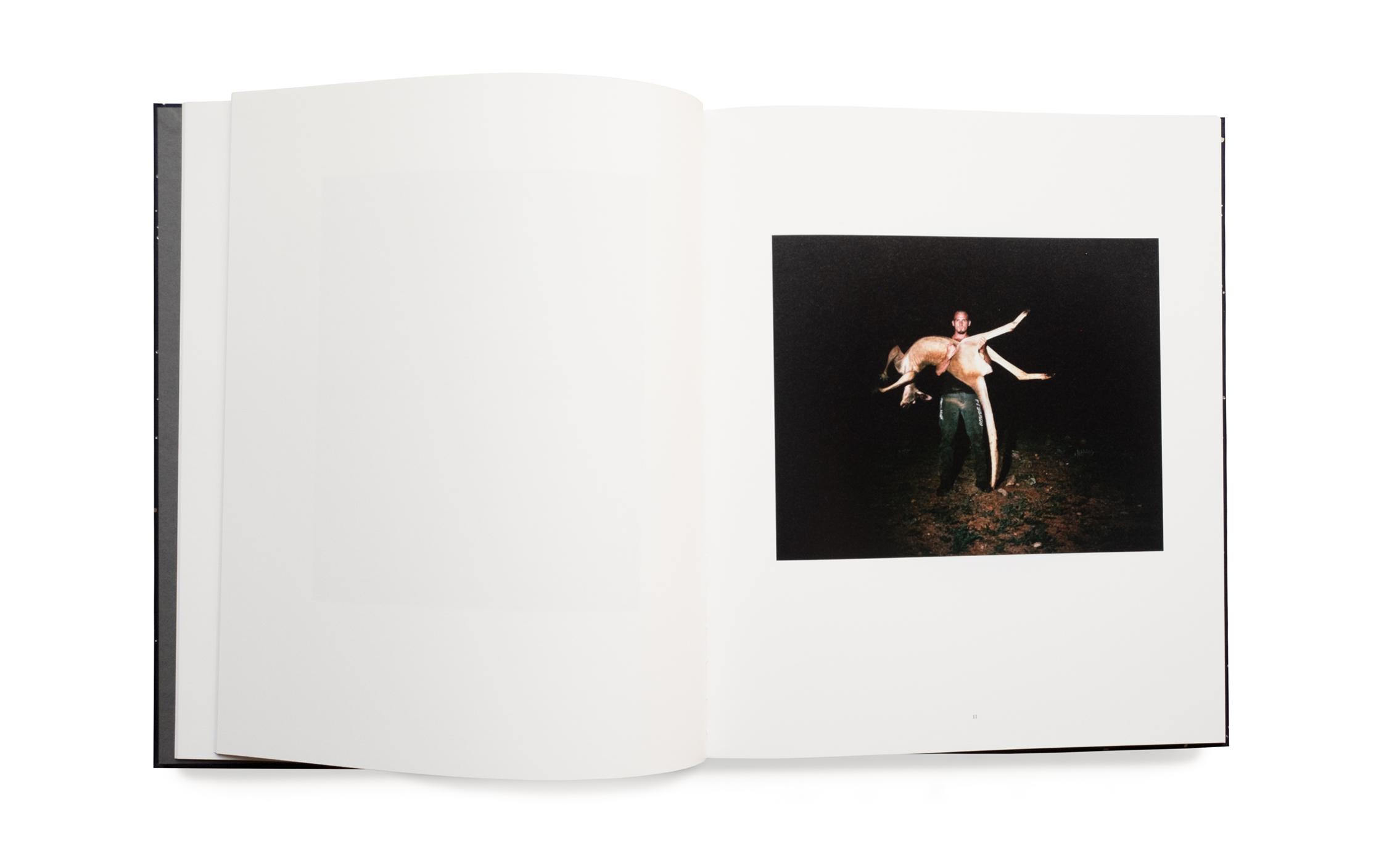

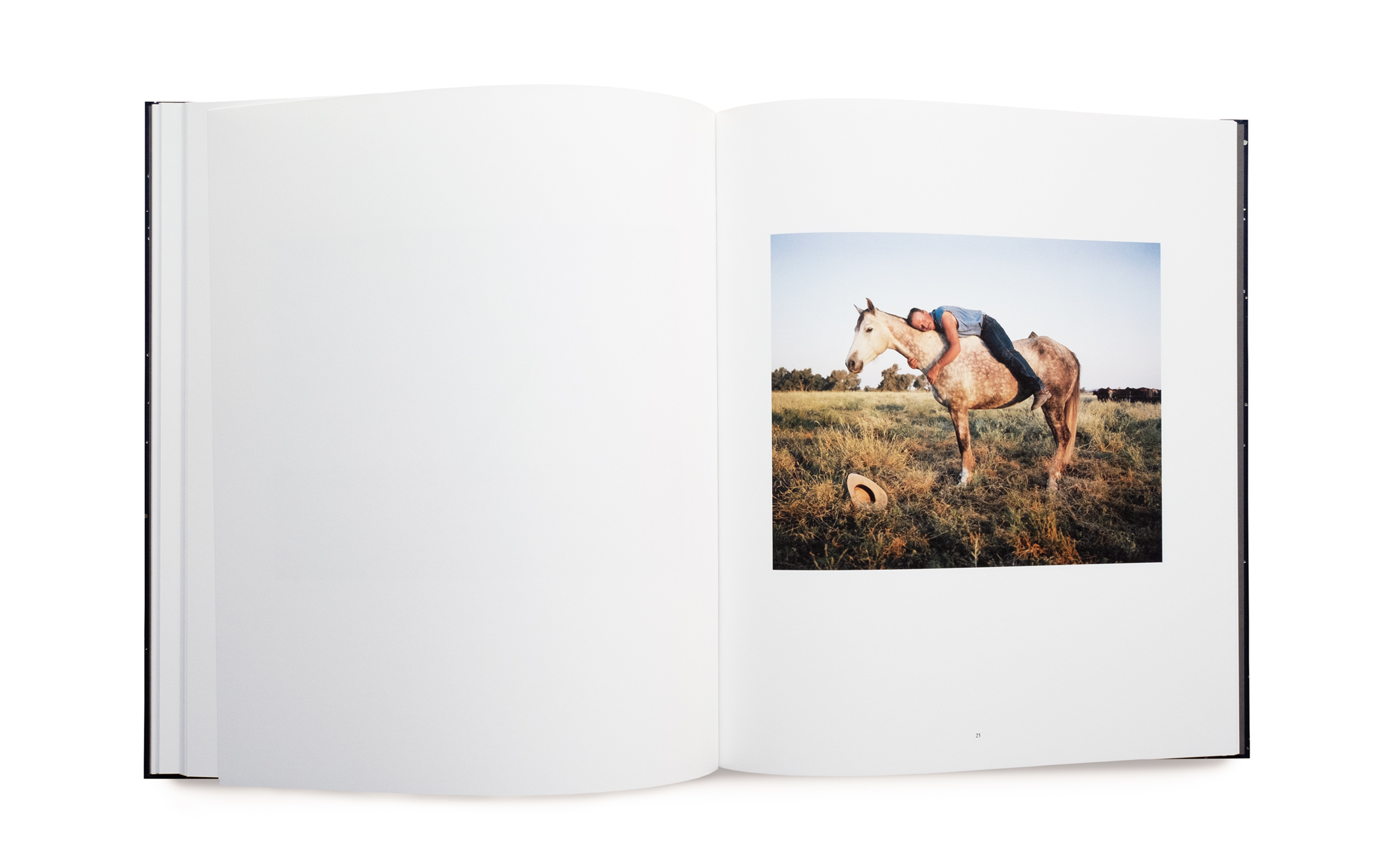

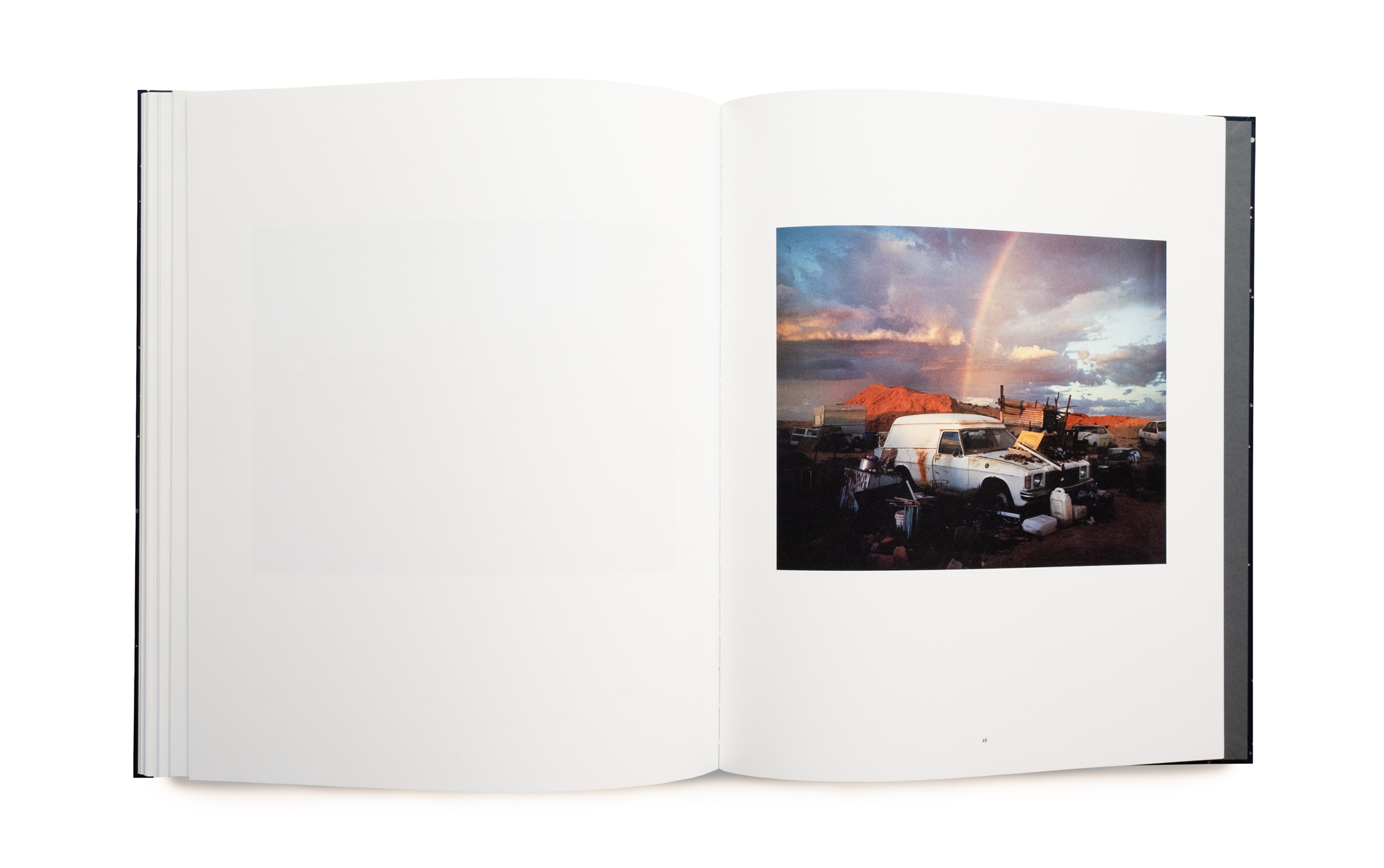

Adam Ferguson’s new monograph is a photographic survey of the Australian bush. Big Sky, published by GOST Books, takes in the fading yet iconic events of rural life, shrinking small-towns, Aboriginal connection to Country, pastoralism, the impacts of globalisation and the adversity of climate change. The series premiered at PHOTO 2024 International Festival of Photography. We sat down with the photographer to find out more about his first publication.

Hi Adam, how would you describe your practice?

I’m a photographer. Sometimes the work is made journalistically, other times it is conceptualised, and occasionally it is commercial. At the core it’s using the tools I have available to tell a story. Although my happy place is exploring an idea or narrative that comes from within.

After working extensively overseas, what led you to creating a series about the Australian Outback?

I’d spent almost a decade living and working internationally as a photojournalist, telling stories about other cultures and contexts, largely through translators. At some point I started to feel disconnected from Australia and my sense of identity was wavering. I’d also lived through traumatic experiences covering conflict in Afghanistan and Iraq. Photographing at home was a form of self-prescribed therapy. I had an overwhelming urge to reconnect with my own story.

At what point did you realise the scope of the project you were undertaking? And did you always consider the project to be presented as a book?

At the beginning I set out to make a portrait project that was inspired by Richard Avedon’s In the American West, but after the first few trips I realised that the human relationship to the land and Country was at the core of the story I was trying to tell. So the work expanded into both portraits and landscapes that were gathered through a series of road-trips in the vein of Robert Frank’s The Americans. The book format was a goal from the outset, which is a little antiquated in a modern context, but it’s my ideal format for long form photo stories. My career was initially inspired by photo books, and specifically the ones I mentioned above, so it was a natural progression to make my own version of those that is specific to Australia.

Big Sky is published and designed by GOST Books in London. How did this relationship come about and how was the experience for you?

I met Stuart Smith of GOST through a colleague earlier in my career and we started a book together that compiled my work from the war in Afghanistan. In the end I wasn’t ready to see that war work clearly and we never finished it. But we kept in touch and when Big Sky was getting towards completion we met in London and he agreed to publish the book. I enjoyed Stuart’s sensibility as a non-Australian and think his distance helped inform a very sober edit. I lost count but we would have had over 40-50 Zoom sessions over a six-month period as we finalised the book. We were able to argue the work in a way that wasn’t personal or combative – our dialogue was simply a fight for the story we both saw. In the end we mostly agreed but I think what we both brought to those conversations made Big Sky a better book.

The series Big Sky is a finalist for the Louis Roederer Sustainability Award, representing Oceania. What message, if any, are you hoping people will take away from the project?

Big Sky didn’t start as a response to the climate crisis – it was for the personal reasons I mentioned. But for the first seven of the ten years I worked on this project Australia was experiencing one of its most severe droughts in modern history, so climate-change was inescapable. The human relationship to the land I was witnessing was becoming increasingly defined by extreme weather patterns. In the last three years that I worked on the project I saw communities affected by bushfire and flood. It’s easy to feel like the climate crisis isn’t already here, especially from the position of an urban city dweller in the developed world. I guess the inherent message is to look at rural communities on the margins, and through this, hopefully, comprehend what a critical time we and our environment is in.

What have been some of your career highlights to date?

Sitting with Daisy Ward, a Ngaanyatjarra Elder in the western desert and hearing stories. Having a US Army colonel send his Blackhawk to pick me up from a remote combat post and then flying over Afghanistan with the pilot asking me where I wanted to go. Knowing that one series of images I made directly helped a group of Nigerian women get education. That’s what comes to mind. Awards and exhibitions are fleeting, but the lived experiences and relationships stay.

And finally, what advice would you give your 15 year self?

I spent too much time as a younger photographer conforming to modes of photography and ideology rather than trying to make my own – so my advice is, don’t be concerned about what other people or the industry is doing or saying, make your own work fearlessly.