Q&A: Atong Atem On Her Limited Edition Print

1.3.23

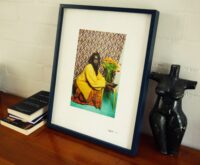

To celebrate the launch of our limited edition print series we sat down with artist Atong Atem to discuss her work, 'Studio '85', drawn from the Surat series. 'Studio '85' will be the first print of the series.

Hi Atong! Can you start by telling us about the concept behind the Surat series?

I was drawn to making Surat from my interest in the history of photography in Africa, and studio photography specifically. I was interested in not quite re-creating but paying homage to family photos as objects, documents of history and a way to preserve tradition and mythology… objects that are important beyond visual importance.

A big part of that was my own family’s history of taking family photos, and how as far as objects go, they were one of the few things we were able to take with us on our journey of migration. However, in creating Surat I didn’t want to just replicate the photos. It felt relevant to make a series of self-portraits; to sit in the fact that the work is my own perspective and my own interpretation of history, and familial history. I wanted it to be surreal with the image of me standing in for different characters in my family, which became a stand in for other families and their different histories with a similar relationship to photography.

Familial, and geographical histories are a big component of your work. Why are those themes important to you?

Geography is important to me because it informs so much of what I do and how I live. As a displaced person I have an intense curiosity about how where I am now in Australia has influenced the way I relate to the world, as opposed to if I had stayed in East Africa, and specifically South Sudan. Being displaced or relocated and no longer having access to our homes has influenced our culture so much. I find it fascinating to investigate that, but also to celebrate what has come out of it despite displacement being such a traumatic, horrible experience.

You've described your photographs as documentation of the performance, can you tell me a bit about your process and what informs your subject matter?

It’s hard to put into words because it is intuitive. It’s informed by so many things that are definitive, like African Studio Photography from the 1960s, that have a very specific feel. It’s easy for me to reference that subconsciously; it’s informed by my family who I know so intimately, and by my feelings, emotions, and place in the world. I forget that I’m making choices because it feels natural, almost subconscious. I’m allowing myself to explore.

I use a lot of textiles, especially as background, to explore that intuitive relationship to colour and how to dress a set. I spend a lot of time doing this, because I tend to do it all on my own. I spend more time setting up the shot than taking the photos, usually multiple hours if there’s face paint, makeup or costume involved. That exploration and play means that when I finally take the photograph, I know exactly what I want to capture – not necessarily a particular photo but rather a recording of the moment. It’s almost like the photos are incidental.

Surat was installed as a huge display at the Department of Treasury and Finance in the Parliament district for PHOTO 2022, and simultaneously on billboards in the streets of Toronto, Canada as part of Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival. What was it like having your work seen at this scale, and by thousands of people who might not normally see your work in a gallery?

I was grateful to have my work exhibited in public and for free. I often address things that people don’t necessarily think they care about but can relate to or find they respond to. It makes sense for the work to exist in public and be shown in accessible ways in terms of scale. I didn’t realise how much impact that would have on my thinking. I’ve since made work that is intentionally large scale. Having the work so big, public and prominent was initially nerve wracking, but seeing how beautiful, strong, and powerful it had allowed me to think about photography outside of what’s been acceptable to me in the past. There’s so much more I can do with it now.

It’s amazing that people were also able to take the work home with them after your photo book for Surat was published, and again with your limited edition print of 'Studio '85'. Why is it important for art to be accessible and affordable enough for people to own?

Art is inherently about the world we live in. It’s for people and the fact that artists can do whatever they want and respond to whatever they want means that interesting ideas exist, that the whole world should have access to. It’s education. It’s politics. It’s spirituality. And it’s a shame that a lot of that is only accessible to a small group of people who perhaps already have access to lots of stuff in general. So why not allow as many people as possible to have access to a world beyond the literal, a world beyond the ‘factual’? It’s exciting to offer beautiful and unique things that don’t cost a million dollars.

Great answer Atong. On a final note, can you tell us about the meaning behind 'Studio '85'; the materials, and components it features and its importance to you?

‘Studio ’85’ references a series of three photos from my family albums of my mum, her cousins, friends and sisters, having their photo taken some time around 1985. They’re doing the traditional African Studio Photography and thinking of that history was really striking to me. There is a direct connection from artists like Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta, all the way through to me, via my parents. I’m continuing a legacy with my photography that’s not about making anything new or different, but about appreciating an existing legacy that I want to be part of.

In the photo my mum is crouching, wearing colourful clothes, and there’s a beautiful backdrop. I wanted to explore if I was my mum now, in 2023, as the subject of a studio photograph, how would that look? What would my influence on creating that image look like? I chose textiles that I have a personal connection with. The background is fabric that I bought the very first time that I took a photo. I was drawn to it because it looks like it’s from the ‘60s.

The process of making the frame for the print was special and intricate too. We spent a lot of time figuring out what colour would sit best with the work. I didn’t want anything neutral because it felt important to respond to the fact that colour is such an important part of my work. We went through several selections to match the exact blue shade that exists in the background and Fini Frames did such an amazing job of respecting the importance of that to me and working alongside me to find the perfect blue. There was a bit of sampling, and everyone had some input, including Elias. But it was unanimous when we landed on the colour because it referenced the palette so well without being overwhelming. I’m so happy with it.