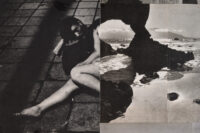

Image: Lillian O'Neil, Compound Falls (detail), 2019

Q&A with Lillian O'Neil

7.5.20

PHOTO 2021 artist Lillian O'Neil reveals how a 15m tall concrete sheep was an early inspiration, and how her intricate montages are preserving a disappearing photographic texture. Look out for her upcoming exhibition at The Commercial and a major new commission with Metro Tunnel Creative Program for PHOTO 2021.

What started your relationship with photography?

My first memory of a photograph is probably a black and white photo that my dad took of The Big Merino in Goulburn. He had a darkroom in the shed and as a kid it was obvious that something mysterious and serious happened in there. There were lots of photos hanging around the house and collections of photos in drawers. I particularly liked looking at the pictures of mum and dad before they had kids.

I don’t take photos myself, but I collect them to make photomontages. As my collection has grown it has become a strange aggregated snapshot of the past 100 years or so. Books like Sexy Ways Women Like and 1972 collide with Inside Apple, 2007, and Australia’s Greatest Pub: 1987. It’s a strange collection and one that offers a lot when it comes to putting a montage together.

Compound Falls (detail), 2019

What is your motivation for making art?

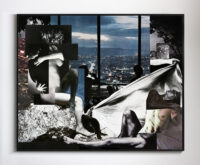

I think, in a small way, by holding on to all these books and magazines I’m helping to preserve a disappearing photographic texture. My books are mostly taken from the pre-Internet era so the material is now generally obsolete. The fragility of the paper, the subject matter and the fading inks suggests passing time and makes them a very precious material. The images stretch from about 1930-2000 and the subjects are far reaching. When I start to assemble a montage I cover the studio floor with a carpet of these images and start looking for links, patterns and repetitions, photomontage has an amazing ability to condense huge amounts of information and it’s the process of making a coherent whole by assembling/puzzling/cutting/combining that keeps me fascinated.

Compound Falls, 2019

How do you plan new projects?

I use the State Library to research, and I spend a lot of time driving around to book fairs, op shops and second-hand book shops to collect material. Then I pile the books up in my studio, scanning and altering the scale, and cut out the pictures that resonate and place them all on the floor. It takes me months to put a large montage together. I really have to sit with the photos and see how they communicate with each other.

How does your lived experience influence your work?

Found images have a way of linking with our own memories. I look through hundreds of images a day and there are repetitions of human poses and patterns of photographic subject that mirror events and gestures in our own lives. Finding these repetitions and grouping them together can be revealing and seems to create a kind of cache of grand gestures and narratives that we all experience concerning love, tragedy, absurdity, etc. Sometimes when I’m making a photo montage it begins with a specific memory linking directly with a found photograph. Then I use the montage process to pinpoint that photograph’s poetic potential by changing its scale, connecting it to other images, altering its context, etc.

The simmer dim, 2018

Who or what inspires you?

The photographers of the images I collect inspire me. They are all there in the work, shimmering below the surface.

What books are you currently reading?

I’m currently reading Love by Angela Carter. It’s about a woman who is deeply terrorised by seeing the moon and the sun in the sky at the same time. She then falls into a relationship with two brothers, one who poetically aligns with the sun and the other with the moon. It’s not going to end well. There are some great lines in it. One that comes to mind is: “A private period impersonating something quite strange.”

How are you spending your time with the current social distancing restrictions?

I recently moved from the city to a farm on Wadawurrung land on the Surf Coast with my partner Dugald Etheredge. I spend a lot of time trying to ignore the sheep that stare silently at us through the windows. My studio is an old courthouse in Geelong and I’m currently the sole inhabitant, usually it would be full, in use as Platform, a youth arts space that has unfortunately had to close for the time being. They had the generosity to reach out to solo artists that could make use of the space. Because none of my usual spots for new material are open, I’m going through boxes and boxes of images that I’ve had in storage and I’ve unrolled all the offcuts and discarded prints that I‘d decided not to use in previous work. I’ve got a show coming up later in the year at The Commercial so I’m puzzling that.

Standing Stones, 2017