Q&A with Danica Chappell

26.5.20

Melbourne-based artist Danica Chappell shares insights into her creative process and inspirations, and how she employs analogue processes to make abstractions. She is currently working on a new commission for La Trobe Art Institute as part of PHOTO 2021.

What started your relationship with photography?

Perhaps this is a commonality, I was given a camera as a gift from my parents at the beginning of my teens. If there was one moment that started my relationship with photography, then it began when I started observing the quality of the images produced from my KodakDisc camera and reviewed these in comparison to those photographs made with the family’s 35mm SLR camera. Every frame from the tiny negatives of the disc camera dispersed light and colour across the print with the appearance of a Pointillist painting. Pretty soon thereafter, I’d seize the opportunity to be outside of the frame capturing the moment rather than being in the photograph.

Coupled with this, was the experience of growing up moving across various regional Victorian towns empowered me to question the nature of things. I would never have known it at the time, looking back I remember being aware of the light, big skies and long horizons, blazing red. Experiencing the environment, dry and harsh in the north, green and wet in the south, walking in Gariwerd (Grampians) and one science class searching a river bed for shell fossils. Constantly navigating new spaces, attuning my senses to new surroundings and communities within them.

What is your motivation for making art?

Exploit lived observations.

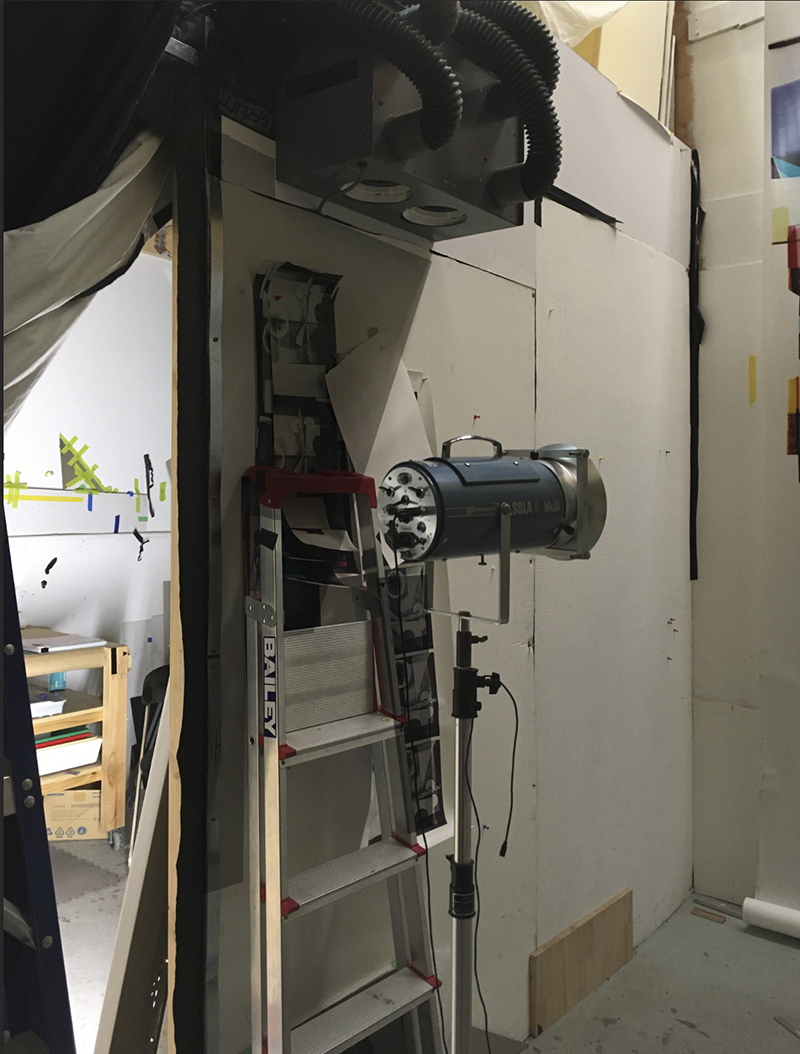

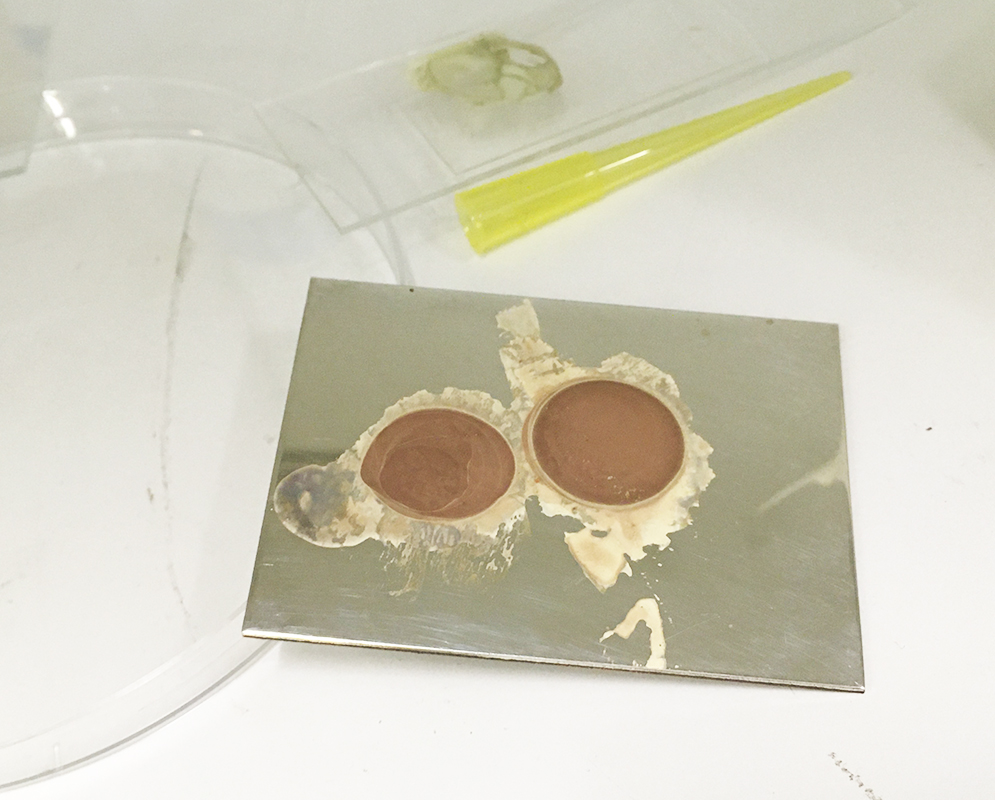

I start with asking what does this photograph want to be, what can one material reveal in relationship with another? Over my career, I have developed a dialogue with the building blocks of a photograph – light, colour, form and the various methods that can fix these as one. Motivation to make art comes from the need to be tactile with the construction of a photograph via the darkroom. I aligned myself with analogue processes very early in my education, then chose to omit the camera from my approach. The darkroom, my body and the photograph are at once an apparatus and a material and cameraless photographs oblige full-body immersion and finger-heavy activity to interrogate the construction of the composition.

Each exposure reverberates a receptivity that impulses momentum, expanding the dexterity in each series to challenge known conventions. Within the language of the photogram, I draw upon inspiration garnered from painting, sculpture and movement. One well-known convention worth pushing against is latency, the unseen inscription mid-construction. For me, light sensitivity is an elastic fissure, where I can cast doubt on conventions and traverse the edges to expose my considerations and the nature of touch in a photograph. An overall direction in a series unfolds from this working method through periods of testing and negotiation with studio detritus. There’s a moment in a work where I reach a point of fullness or perhaps exhaustion, not only in the body but in the composition. That enables the photograph to claim its final position in the frame, transferring its completeness to the eye.

Seeing the final photograph offers complex energy that draws attention to the pictorial and processual abstractions that have taken place and not easily deciphered. The viewer becomes an active participant in the work; their time, motion and engagement animate their relationship with the work through a tactile eye.

How do ideas relating to 'The Truth’ factor into your practice?

A photograph holds a truthfulness to a process but is deceitful in its image. Appearance, scale, tone, colour and time (to name a few) are accomplices in this deception. The notation from my darkroom activity for each work, as an example, fabricates a record of each abstract construction however can only be an approximation of the factual. We have come to accept that there is an inherent slippage in a photograph.

By whatever means of the long list of methods that articulates the features in a photograph, photography’s path through obsolescence and reinvention can be distilled into one truthful fact. Light touches a light-sensitive substrate and a photograph is an object of evidence to this fact. My practice moves loosely across all aspects of photography’s wonderfully complicated history. Speaking from the perspective of analogue processes used to make abstractions, the darkroom craft and the subject are in the hands of the maker, the navigator, the performer. Truth is not found in what the photograph depicts but is embedded in the construction of the object itself.

In this post-internet age, how do you see the viewer in relation to your artwork?

Being present at a live performance, no matter the type, the audience has a direct connection to the artist interacting with their art form. It’s immediate and indelible. A viewer may experience photographs on a variety of platforms, each expressing intent and purpose of what is being observed. My practice is generated out of the tactile engagement with materials and operates with a relationship to a physical presence. A person tethers themselves to my darkroom interventions, scripted and scored onto light-sensitive substrates when they stand in front of and moves around the photographs themselves. The hope is, that no matter how any art form is distributed and received, what is important is the experience of looking and thinking.

Danica Chappell, Thickness of Time, 2018-19 at Heide Museum of Modern Art. Photos: Christian Capurro.

How do you go about developing new projects?

Leading up to the exhibition ‘Thickness of Time’, I visited various archives of museums and libraries looking at numerous artefacts of historical photographic processes. This was a tremendously enriching opportunity. Research and ideas infiltrate the making process; there is the presence of an unrelenting, evolving question about time that I carried through to the making of that body of work. Photography’s history of transitioning processes, generate ideas of obsolescence and cloaking – the phasing out of one, into another – facilitated the feeling that there was more time to be had in an exposure.

Being in constant contact with the darkroom is important for how a series unfolds. I start with a bare substrate in the dark and program a set of manoeuvres to make it feel complete somehow. An overview based on a technique sets the initial direction, then the making is informed by the negotiation of materials applied. However, I’m flexible with the application and the shape of the work develops from there. There is a lot of time testing, looking and repeating actions to expand the form. The architectural space of a gallery is one aspect under consideration as it has a known logic for the passage of moving bodies. Generally, I will make excursions to the gallery when preparing a solo exhibition as a way of feeling features in the space and work in a way that these can be exploited.

What inspires you?

Visually immersed in my surroundings, I might see an object or the representation of a form and think about that as an action or a colour concerning light. I take inspiration from many influences, some are:

Touch.

The feel of light.

The feel of latency.

A body filling a space with movement.

Extreme shifts in scale.

Colour shifts

Brush-strokes on a painting.

The articulated planes.

The connection between the bowing and finger action on the violin.

Opacity and density.

Moving in darkness.

Seeing all sides of an object.

What is in your research scope/ What are you currently reading?

Time to think is as urgently necessary and productive as the time to make an image.

I’m an inconsistent reader, dipping in and out of book chapters and favouring articles, rather than consuming an entire book at a time. In front of me at the moment are a few articles on cleaning and conservation of Daguerreotypes of particular interest is ‘plate measles’; Andrea Eckersley’s ‘The Event of Painting’; Joyce Tsai’s ‘László Moholy Nagy: Painting after Photography’; and a few articles on the early photography from La Lumière of particular interest is Gustave le Gray.

What is your favourite website?

www.slv.vic.gov.au/search-discover features a lot in my browser history, SLV offers amazing access to online databases, e-books, art magazines and articles which I would be lost without. Recently with Covid-19 social distancing in place, I had reconnected with ambient TV in the background of my workspaces, such as the webcam of the River Maas, Rotterdam, and the Dunedin Albatross cam.

What music are you listening to?

Music is vital in each body of work. Some playlists are on repeat while working in the darkroom. Like a metronome, music keeps my rhythm and recall focused. I’ll listen to anything and everything – though perhaps I’m less engaged by wind instruments, although I don’t mind live jazz. Of particular enjoyment is being up close in any live performance where you can witness the instrument (electric, synth or acoustic) as an extension of the musician’s body.

If the work you are presenting at PHOTO 2020 was a song, what would it be?

Long, delicately robust and chaotic with opposing elements and an intermittent scatter of improvised lyrics about the undocumented reality that sits between frames.

How are you spending your time with the current social distancing restrictions? Has this motivated you in a way that you might not have expected?

I have been thinking a lot about friends and colleagues abroad, I feel tremendous grief for the global loss of life and this has undoubtedly distracted my focus, for sure. I am continuing to work through elements for ‘Far from the Eye’, my exhibition for PHOTO 2021 and the extended timeline has enabled me to continue planning and evolving my ideas, in conversation with Dr Donna Whelan who I will be working with on a commission for La Trobe Art Institute. I look forward to sharing this work with everyone in 2021.

How do you hope the broader community will overcome this unique challenge?

Visual artists are the masters of lateral thinking, adaptation, compromise, communication and finding workarounds while remaining faithful to their intent and their craft. Without hesitation, I hope Australians can emerge from this crisis as a more thoughtful, respectful, generous, open and supportive nation that nurtures its arts and culture sector across all platforms and communities.

Danica Chappell will be exhibiting at La Trobe Art Institute as part of PHOTO 2021 from 27 January to 31 March 2021. All images courtesy Danica Chappell.