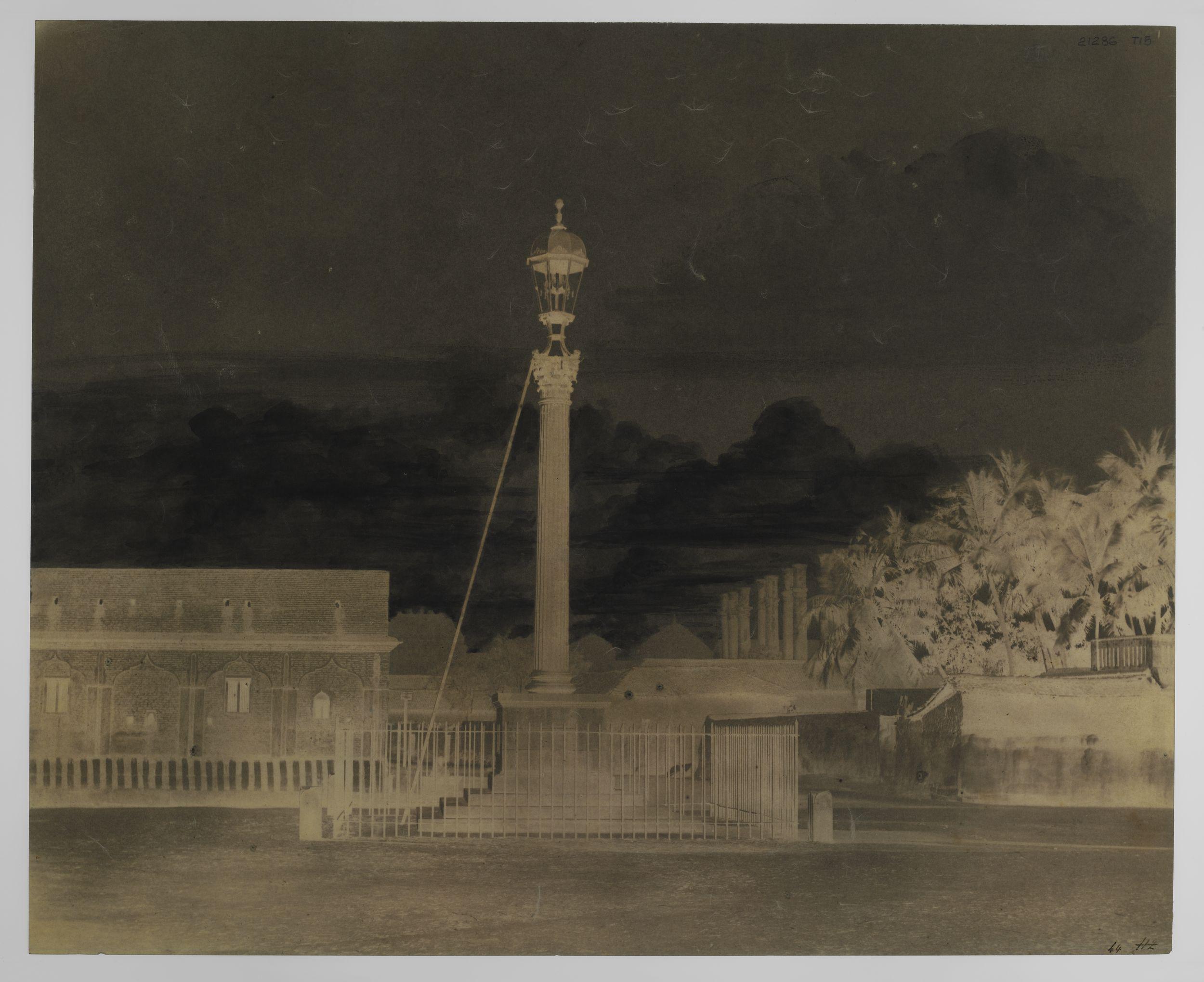

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre , Boulevard du Temple, c.1838, daguerreotype

A Brief History of Photography and Truth

28.10.20

The photograph has historically been viewed as an authentic, factual representation of truth. In more recent years, this long-held belief has been questioned through the prominent coverage surrounding manipulated and faked photographs, an element of the post-truth era. Reflecting on early photographic experiments and the rise of portraiture, Catlin Langford – the V&A Curatorial Fellow in Photography, supported by The Bern Schwartz Family Foundation – reminds us how photography's complicated relationship with the truth is not a new condition.

The photograph has historically been viewed as an authentic, factual representation of truth. In more recent years, this long-held belief has been questioned through the prominent coverage surrounding manipulated and faked photographs, an element of the post-truth era. [1] The conversations surrounding faked imagery remain as relevant as ever. In mid-June 2020, in amongst a rolling coverage of the significant Black Lives Matter movement, Fox News was accused of manipulating photographs depicting events surrounding the protests, including the formation of the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ) in Seattle, United States. The digitally altered photograph was pronounced unethical, misrepresentative and the antithesis of the truth-telling required and expected of documentary photography. [2]

The blurring of the line between truth and artifice in photography is widely attributed to the invention of Photoshop in 1990. The cultural resonance of the photo-manipulation programme is demonstrated by the fact that to ‘photoshop’ is now a verb meaning to alter photographs, so embedded it has become in our daily lives and understandings. Yet, even in contemporary culture, the photograph is still perceived as a way to authenticate experience and events, consider the contemporary mantra, ‘pics, or it didn’t happen’, a modern extension of the idea ‘the camera never lies’.

This push and pull relationship between photography and truth, the blurred boundaries of fact and fiction, has much earlier origins than the advent of Photoshop, extending to the beginning of the medium itself.

The Photographic Eye in the Nineteenth Century

Whilst evidence exists of earlier photographic experiments, it is widely agreed that photography was invented in 1839. In this year, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851) and William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-77) announced their photographic inventions. Daguerre gave the world the daguerreotype, a beautiful, unique photograph produced on a slither of highly polished, photo-sensitive silver-plated copper. Announced weeks after the daguerreotype was Talbot’s photogenic drawings that produced photographic images on silver-salted paper. Talbot’s invention laid the foundations for the salted paper print and calotype, the latter introducing the notion of the photographic negative and positive.

Photography was understood to offer the opportunity to capture images of the world in what was perceived as the height of realism and truth. However, the inherent restrictions of the medium meant that photography was unable to capture reality exactly as shown in nature. Daguerre’s Boulevard du Temple (c.1838) is attributed with being the first photograph to depict people. The daguerreotype depicts a street scene. Towards the lower left of the work, a man stands, his leg slightly raised as his shoes are cleaned by a shoe shinier. Other figures and traffic would certainly have been present on the notoriously busy boulevard. However, this movement and activity could not be captured owing to the slow processing times of the daguerreotype, then lasting approximately seven minutes. As the photograph does not capture the full reality of the scene, can the work be considered a truthful, realistic image? Boulevard du Temple illustrates the limits of photography and the need for continued development and refining of the photographic medium to meet the desired standard of realism.

In response, the 1850s saw significant technological developments that increased the capacity of photography to accurately render a scene. In 1850, Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard (1802-72) first displays his invention of the albumen print. The albumen print was the most popular photographic technique of the nineteenth century, understandable, owing to its production of wonderfully rich, brown-toned photographs. The albumen print complimented the wet collodion glass plate, invented in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer (1813-57). The sensitivity of the wet collodion negative limited exposure times to mere seconds, producing beautifully sharp and defined images. Through the negative multiple prints could be made of the same work. Yet, there were problems. Wet collodion negatives had to be developed on site, meaning photographers working externally needed to travel with a cumbersome, portable darkroom. Furthermore, the wet collodion’s lack of sensitivity to blue light meant the sky and the sea could not be accurately captured on the same plate. Photographers thus had to be adaptive and devise methods within the boundaries of what was technically possible.

Owing to such technological restrictions, during the early years of the medium photographers turned to editing works to reflect the reality, or vision, of what they perceived to be accurate. Gustave Le Grey (1820-84) was widely praised for being able to capture both the sky and the sea in his series of seascapes taken in the mid-nineteenth century. In 1857, acritic for the journal La Lumière, declared Le Grey’s photographs ‘the event of the year’. [3] This feat was only accomplished through combining two negatives to create one photograph, one exposed for the sea, the other for the sky. Occasionally, Le Grey combined negatives taken at different locations, creating brilliant, composite visions of make-believe scenes. In a similar vein, Linnaeus Tripe (1822-1902) painted clouds on to his paper negatives as they could not be captured during the slow exposure. Through his creative additions, Tripe conveyed a sense of the landscape he had perceived during his travels in Asia but was unable to replicate through the then available technologies. [4] These examples indicate the early use of retouching and editing techniques in the foundation years of photography.

The technical constraints of the medium also had an impact on documentary photography as events could not be easily captured in real time. In the nineteenth century, documentary photography, in terms of the contemporary understanding of being ‘on the street, in the fire’, was not possible owing to exposure times and the difficulty in developing plates on site. Photographers thus chose to stage scenes to convey a sense of the events they had witnessed or to match descriptions in the contemporary press. As noted by Susan Sontag (1933-2004), ‘Not surprisingly many of the canonical images of early war photography turn out to have been staged, or to have had their subjects tampered with’. [5] A notable example is the widely debated photograph Valley of the Shadow of Death by Roger Fenton (1819-69), taken in 1855, when Fenton was commissioned by the publishers Thomas Agnew & Sonsto document the Crimea War (1853-6). It remains contentious, but evidence shows that Fenton and his assistant Marcus Sparling (1822-60) rolled cannon balls into the valley. This addition heightens the power of the photograph, communicating a sense of the cannon fire and danger of war to faraway readers. Accusations of staging have similarly been directed at Felice Beato’s (1832-1909) haunting photograph Sikander Bagh, Lucknow, taken in 1858. The photograph portrays the aftermath of the massacre of over two thousand mutineers, a horrific event that had occurred the previous year. Given the time delay, it is thought Beato and his assistants exhumed skeletons to compose the photograph. [6] Whilst this construction and artifice may seem a clear departure from the truth, in these instances the photographers were attempting to construct a scene that spoke to their perception of the events that had occurred and create a truthful representation.

Staging was also a key technique for photographers trying to assert the artistic potential of photography in the nineteenth century, a time when the status of photography was greatly contested. Photography was famously discounted as an art form in an 1857 essay anonymously penned by Lady Elizabeth Eastlake (1809-93). In the widely distributed essay, simply entitled Photography,Eastlake stated photographs were created through the action of the sun and were thus objective, mechanical creations without subjective, artistic value. She surmised that photography was better suited to producing ‘cheap, prompt and correct facts’. [7] Her statement did not consider the rise of photographers creating consciously artistic photographs through staging or using multiple negatives. These photographers viewed themselves as artists, and their works aligned with popular artistic themes and compositions of the time, asserting themselves within a pre-existing artistic narrative. Henry Peach Robinson’s (1830-1901) 1858 work Fading Away is a notable example. The photograph depicts a young, sickly woman, seemingly taking her last breath in the company of family and her fiancé. The work was staged and constructed through combining five separate negatives. Critics of the time believed the work betrayed the truthfulness of photography. Whilst a work of photographic fiction, the photograph reflected on the reality of soaring death rates from tuberculosis in Victorian Britain. [8] Robinson’s photograph blends truth and fiction and asserts the artistic quality and potential of photography in defiance of contemporary debates on photography’s lack of artistry.

Eadward Muybridge, The Horse in Motion, 1878

The continual experimentation and development of camera technologies encouraged further discussion on the place and role of photography. Ideas of perception were regularly questioned, including the ability of the camera to “see”. As noted, in the years following the invention of photography in 1839, the human eye certainly perceived more than the camera could. With the rapid development of camera technologies during the mid-nineteenth century, the camera begins to capture more, things previously considered impossible. In the 1870s, Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) creates a series of images of a horse galloping. His photographs illustrated that at some stages of the gallop, all four hooves of the horse are off the ground simultaneously. The human eye is unable to recognise, or read, this action. The camera could now ‘see’ more than the human eye possibly could. If the camera ‘sees’ more than the human eye, does this make it more truthful, or less? The debates surrounding the place and role of photography existed alongside the significant commercial expansion of photography based on the strong desire to capture an apparently truthful likeness of oneself.

Portraiture, Perceptions, Power and Play

Perhaps the most appealing aspect of photography following its invention in 1839 was the opportunity it offered to produce portraits depicting a true likeness, what we would now call a ‘photographic likeness’. Initially sitters were required to stay completely frozen for a few minutes to account for long exposures. Whilst potentially difficult and boresome, the photographic portrait was a complete revision of the previous method of commissioning a painter to create a portrait at considerable financial cost and time commitment. Understandably, portrait photography proved to be immensely popular, with commercial photography studios experiencing a roaring trade. The medium was praised for producing a wholly accurate portrayal of a person, a mirror-like image. Whilst these images could perhaps be understood as truthful, there was room to move in the photographic format, to develop and present different visual identities and personalities through self-fashioning, staging and creative intervention.

Hippolyte Bayard, Le Noyé, 1840

The first known faked portrait, dating from 1840, shows the power of staging to convey a strong statement. Daguerre is widely credited with inventing photography in France but there were other practitioners and inventors working on photographic methods and technologies in the same period, including Hippolyte Bayard (1801-87). François Arago (1786-1853), a friend of Daguerre, encouraged Bayard to delay the announcement of his photographic invention. Consequently, Bayard’s invention and contributions to photography were ignored, eclipsed by the celebrations surrounding the daguerreotype. In response to his alleged injustice, Bayard staged a portrait entitled Le Noyé (Self Portrait as a Drowned Man) in 1840. The portrait depicts the artist shirtless, slumped in a chair, his eyes closed to signal his recent demise. It was the first faked, staged portrait and was accompanied by a statement indicating Bayard’s turn to suicide because of the lack of recognition he received by the French government for his role in the invention of photography. The statement read:

The corpse which you see here is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process that has just been shown to you. As far as I know this indefatigable experimenter has been occupied for about three years with his discovery. The Government which has been only too generous to Monsieur Daguerre, has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself. [9]

Bayard’s contributions to photography remain largely unrecognised, but this early portrait is significant, showing the possibility to play with and manipulate the photographic portrait despite the apparent inherent truth presented in the medium.

In 1854, the portrait photography trade was revolutionised by the invention of the carte-de-visite by André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (1819-89). The carte utilised the recent inventions of the wet plate collodion negative and albumen print, offering quick and cheap portrait photographs. Up to eight photographs could be taken on the same plate, allowing individuals to pose in eight different ways, or guises. The preferred image was printed, often on mass, and mounted on cardboard the size of visiting card, giving the invention its name. Cartes were commonly distributed to friends and family to signal personal relationships. Realising the popularity and appeal of the medium, celebrities, royalty and notable personalities sold their image as cartes, allowing people to cheaply purchase portraits of their favoured individuals. The invention was a runaway success. In 1861, over 300 million cartes were sold in England alone, the craze declared ‘carteomania’. [10]

Anson Bros., Hobart (studio of), Mrs Hooper’s boy, aged three, carte-de-visite, 1878-1880 © National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Presented through the NGV Foundation by John McPhee, Member, 2003. This digital record has been made available on NGV Collection Online through the generous support of Professor AGL Shaw AO Bequest.

Charles Jacotin, No title (Soldier in uniform), carte-de-visite, 1890s © National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Gift of John McPhee, 1994. This digital record has been made available on NGV Collection Online through the generous support of the Bowness Family Foundation.

Whilst cartes have been largely criticised for their monotonous and formulaic appearance, this fails to see the flashes of creativity and construct that appear in some works. In terms of the carte, the power balance between photographer and sitter was largely within the sitter’s court. The sitter could dictate the pose, costume and interact with the props to their desired effect. [11] Without strict confines, individuals drew on their creativity to create images of pure artifice: people pretending to row boats on dangerous waters, bodies popping out of mirrors and heads floating mid-air. But there are also more nuanced examples of deception, individuals playing with their self-image, performing accepted and desirable aspects of class and status that did not necessarily reflect their true situation. This use of the medium, as social performance and construct, has been compared to the contemporary social media. [12] There is thus a sense of artifice and performativity as sitters inhabit a world and image of their choosing.

The reproducibility and commercial nature of the carte made it an effective propaganda tool to broadcast specific ideas, including as a means of reinforcing colonial ideologies and power. In terms of the power balance between sitter and photographer, the reverse relationship occurred for individuals of non-Anglo backgrounds, who were often photographed in a capacity outside of their control. This included faked and staged racist imagery that perpetuated ideas of criminality, idleness and savageness, especially notable in images created of individuals from African backgrounds. These cartes served as a mean of enforcing the importance of colonialization and white superiority and were especially popular in the US in the wake of the American Civil War (1861-65). The racist cartes form a direct contrast to the surviving examples of cartes of African American civil war soldiers and notable personalities, including Sojourner Truth (1797-1883) and Frederick Douglass (1818-95). During his lifetime, Douglass was photographed 160 times, making him the most photographed American of the period. [13] Like Douglass, cartes of Truth proved popular, enabling her to live on the profit; as she declared ‘I’ll sell the shadow to support the substance’. [14] These stories and works defy the narrative that Abraham Lincoln (1809-65) ended slavery: there were already freed slaves, and the photographs testify to this fact. [15]

James Tylor, Twinkling eyes of cunningness and ferocity, 2013, Becquerel Daguerreotype. From the series Voyage of the Waka and, the Origin of the Dreaming.

In the same period, photographs of Indigenous Australians were a popular commodity both in Australia and abroad. The works were produced largely under exploitative conditions and the presentation of individuals was commonly dictated by others, without reference to the sitter’s specific culture. [16] The photographs were purposefully derogatory, showing Indigenous Australians as a passive, exotic people, frozen in time and disengaged with the changing world around them. The photographs intended to reinforce European supremacy and the continued control of Aboriginal people. As Peter Quartermaine states ‘[p]hotography is here no mere handmaid of empire, but a shaping dimension of it’. [17] The photographs neglected portrayals of the rich, vibrant culture and significant contributions of Indigenous Australians to the land, economy and society. [18] The popularisation of social Darwinism in the latter nineteenth century was seen to give scientific support for ideas of conquest. Helen Ennis notes the theory ‘argu[ed] that Aboriginal people occupied the lowest rung of the evolutionary ladder. The dying out of their race could thus be justified as a natural, biological process’. [19]

![Image: Patrick Waterhouse, [Let’s Go to Mining. Restricted with Dorothy Napurrurla Dickson, Sabrina Nangala Robertson, and Julie Nangala Robertson], 2014 – 2018 © Patrick Waterhouse/Warlukurlangu Artists](https://photo.org.au/api/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Patrick-Waterhouse-200x133.jpg)

Patrick Waterhouse, Let’s Go to Mining. Restricted with Dorothy Napurrurla Dickson, Sabrina Nangala Robertson, and Julie Nangala Robertson, 2014 – 2018. © Patrick Waterhouse/Warlukurlangu Artists

Some of these injustices of photography as a tool of oppression are being addressed by contemporary artists and photographers in their work. In his series Voyage of the Waka and, the Origin of the Dreaming, artist James Tylor (b.1986) reflects on this history and Darwin’s documentation of Indigenous people, part of his wider interrogation of the way Australia addresses its own colonial history. [20] The interest in images of Indigenous Australians continued throughout the nineteenth century, evidenced by the significant popularity of the 1899 publication The Native Tribes of Central Australia by Sir Spencer Baldwin (1860-1929) and Francis James Gillen (1856-1912). The publicationfeatured photographs of Indigenous Australians, as well as images of Aboriginal sacred sites and the dead, infringing on Aboriginal cultural belief. Patrick Waterhouse’s (b.1981) seriesRestricted Images reflects on this history. Produced in collaboration with the Walpiri, the works ‘symbolically return to these communities’ agency over their own images’. Waterhouse views the works as part of a wider inquisition, considering ‘how we tell the stories of the history of colonisation and the forming of a nation’, which includes the role of photography, and staged imagery. [21]

The widespread commercialisation and interest in portrait photography during the nineteenth century, combined with the relative lack of knowledge surrounding the medium, provided ample opportunities for fraud, perhaps best demonstrated by the thriving trade of spirit photography. William H. Mumler (1832-84) was the first significant practitioner of spirit photography, having discovered the technique by accident when developing a negative featuring a double exposure. The presence of two people within the frame, one appearing as if a ghostly apparition, led Mumler to formulate the practice of ‘spirit photography’. He opened a studio in Boston, New York, United States, working in tandem with a medium. Utilising the double exposure technique, Mumler added other, ghostly human presences to portraits of expectant sitters. Mumler benefitted from a large and eager audience of people who had lost loved ones in the American Civil War and wished to possess one last photograph with them. His business was a success, inspiring others to adopt the profession. But with greater public awareness, was greater suspicion. In April 1869, Mumler was tried for fraud. As noted in the press, ‘he swindled any credulous persons, leading them to believe it possible to photograph the immaterial forms of their departed friends’. [22] He was acquitted, but this cast significant doubt over his practice and he was unable to rebuild his business.

![William H. Mumler William H. Mumler,

[Unidentified woman with male "spirit" pointing upwards], 1862-75, albumen print. Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program.](https://photo.org.au/api/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/William-H.-Mumler-124x200.jpg)

William H. Mumler, Unidentified woman with male "spirit" pointing upwards, 1862-75, albumen print. Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program.

The ability to manipulate photographs, however, later became a selling point for many commercial photographers who offered to ‘retouch’ portraits. The position of ‘retoucher’ was a popular photographic profession around the turn of the century, at the height of popularity of studio photographer. Utilising brushes and knives, the photographic negative was altered to produce the desired effect: chins removed, waists trimmed, and wrinkles softened. The profession was largely undertaken by women who were perceived to naturally understand the needs of a sitter and had the feminine, delicate touch required for manipulating negatives. The experience of working in photography studios inspired a selection of women to adopt the profession of studio photographer, including Dorothy Wilding (1893-1976). Reflecting on her profession, Wilding stated retouching ‘enable[d] me to produce a portrait as the lens of my own eye saw it, and not as the lens of the camera’, producing a ‘fairer representation of a sitter than it would be if a negative were left alone’. [23] Wilding’s statement relates to the belief that by seeing more than the human eye, the camera, and by extension the negative, is not truthful. The commercial photography studio remained an essential service until the wider democratisation of photography via the invention of the Kodak No. 1 camera in 1888, effectively putting the camera into the hands of the people and broadening the narrative of photographic history.