Ruth Orkin, American Girl in Italy, 1951

A Brief History of Photography and Truth

28.10.20

In the second part of this essay, Catlin Langford – the V&A Curatorial Fellow in Photography, supported by The Bern Schwartz Family Foundation – continues to explore photography's complicated relationship with the truth. Here Langford charts the period from the release of the Kodak No. 1 camera and the Cottingley fairies through to Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother and Joseph Stalin’s rewriting of history.

Photography for the People

In 1888, American inventor George Eastman (1854-1932) released the Kodak No. 1 camera. Through use of flexible, dry-plate film the No.1 camera was lightweight and produced near instantaneous ‘snapshots’. It was marketed as easy, with the company offering to process and print the photographs and reload the camera at their factory, summarised in their famous slogan ‘you press the button, we do the rest’. With the 1900 release of the Kodak Brownie camera, costing a mere US$1, camera technologies were now widely available and accessible to all. Kodak emphasised this by advertising the Brownie camera to children through various campaigns, including through the elfin ‘Brownie’ character, reinforcing the notion that photography could now be accessed by everyone.

The opening up of photographic technologies facilitated the use of cameras by children, leading to one of the most famous examples of camera trickery of the 20thcentury. In 1917, the cousins Elsie ‘Iris’ Wright (1901-88) and Frances ‘Alice’ Griffiths (1907-86) took a series of photographs in their hometown of Cottingley, Yorkshire, Britain. The photographs depicted the girls, then aged 9 and 16, with fairies who flittered, danced and played around the girl’s faces. By 1919, the photographs had entered the public sphere, inspiring great interest, as well as significant support from the author and noted spiritualist Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930). As a means of testing the photographs’ authenticity, the cousins were asked to take further photographs of fairies. [24] They obliged, producing another set of fairy photographs in 1920. News of the photographs were sent to Doyle, then in Melbourne, Australia. Doyle recounted:

I was surprised, therefore, as well as delighted, when I had his letter at Melbourne, informing me of complete success and enclosing three more wonderful prints, all taken in the fairy glen. Any doubts which had remained in my mind as to honesty were completely overcome, for it was clear that these pictures, specially the one of the fairies in the bush, were altogether beyond the possibility of fake. [25]

Despite sustained pressure throughout the 1960s and 1970s, it was only in 1983 that the cousins revealed the photographs were fakes, constructed through cardboard cut-outs and hatpins. [26] The embrace of the photographs at the end of World War One (1914-18) is perhaps similar to the embrace of spirit photography in the wake of the American Civil War. [27] In the wake of the devastating war, people wanted something to believe in, with photography offering basis for this belief.

By the end of the 1920s, the practice of ‘snapshot’ photography was an accepted and expected part of the family life, seen as an essential means of recording familial memories. There is a perception that snapshot photographs, in their instantaneity and informality, are completely sincere. This ignores the clearly managed and often repetitive compositions, the controlled elements within the frame and the curation of subject matter within the family album that primarily only displays personally significant and appealing moments, neglecting difficult subjects. The notion of the snapshot’s supposed honesty and sincerity is referred to by Patricia Holland as a ‘deceptive innocence’. [28] If one considers Instagram or Facebook photograph posts as the contemporary extension or replacement of the snapshot album, then it can be clearly understood that editing and selection, if even trickery, played a role in the snapshot and album, showing a highly edited version of life.

Colourful Realities

When we consider the snapshot album of the early twentieth century (1900-50), the vision is one of black and white photographs framed on a black page, however, by this time, colour photography was firmly established. Prior to the invention of colour photography, there were ongoing debates regarding the realism of the photographic medium given it could not truly produce a realistic vision of the world owing to the absence of colour. However, more recent thought tends to perceive black and white, monochrome photographs as being inherently truthful, sincere and serious, somehow more ‘real’, whereas colour is perceived as lurid and unrealistic.

The absence of colour photography throughout the nineteenth century inspired commercial enterprises and amateurs alike to turn to hand-colouring and tinting as a way of enhance the realism of their images. The hand-colouring of portraits was particularly popular, and many portrait studios offered to hand-colour works at additional cost to replicate a ‘lifelike’ appearance. [29] As evident from surviving examples, hand-colouring largely had the opposite effect. The works can appear garish and unnatural. This was an early form of manipulation, similar to Tripe’s addition of clouds, and was a means of creating the vision perceived to be the truth in the absence of suitable technologies. Understandably, there was a strong desire to actualise colour photography.

The answer to accessible, realistic colour photography was provided in 1904 with the announcement of the Lumière Autochrome, later released commercially in 1907. The invention, created by the Lumière brothers Louis (1864-1948) and Auguste (1862-1954), was the first commercially viable and available colour photography medium. The invention was acclaimed as the most realistic and truthful photography medium; as a 1911 article declared ‘we have reached a point where nature’s colours can be secured by a direct camera exposure similar to the taking of ordinary photographs…It may be regarded as the highest development of modern colour photography.’ [30] The praise was despite clear issues with the autochrome’s reproduction of colour, and the propensity for photographers to alter the plates during processing. For instance, John Cimon Waburg’s (1867-1931) photographs of Peggy in the Garden, dating from 1908, waspurposefully under-processed to create a hazy, artistic effect. Colour photography greatly improved over the following years, including the widely known Kodachrome, released in 1935, that came to replace the autochrome. These methods were praised for their depiction of realistic colour, but in these instances the colour is created through various chemical concoctions, each medium differing from others, with a propensity to change and fade over time. In this respect, it is worth considering whether the colour was ever truly faithful to nature.

In recent years, there has been a movement to ‘colour’ monochrome photographs through digital means. ‘Colorized History’ is a trending topic online, gaining significant traction and inspiring others to adopt the practice. [31] These digitally coloured photographs are praised for bringing history to life, humanising the past and making the images relatable- a truthful account of history as it was experienced. Jordan Lloyd of the company Dynamichrome notes ‘seeing something from that long ago in colo[u]r helps us understand it a little better because colo[u]r plays a major part in how we interact with the world’. [32] However, there is an argument that by colouring the photographs this goes against the truth of the original image, in its black and white format, and removes it from its initial narrative and context. This is certainly true of the colouring of iconic images that defined and told the story of the twentieth century through the emerging field of documentary photography.

Staging Truth

As a result of increasing flexibility and manoeuvrability of photographic technologies, documentary photography became a key means of recording world events in the twentieth century. Despite the ‘documentary’ nature of the works, instances of manipulation and staging exist, including among iconic images that define the twentieth century. The famous photograph Lunch Atop a Skyscraper, appeared in the New York Herald Tribune in 1932. The photograph was meant to be seen as a candid insight into the construction workers casual, but daring, lunchtime break, precariously balanced nearly 300 meters over the city of New York. It was later revealed the workers were encouraged to pose, the atmospheric photograph purposefully orchestrated to advertise the Rockefeller centre.

During World War II (1939-45), photography enabled critical moments of the action to be captured and these images remain essential to our understanding of the conflict. Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, dated 1945, by Joe Rosenthal (1911-2006) depicts six United States marines raising the American flag on Mount Suribachi, Iwo Jima. The photograph made the front page of newspapers and became a defining image of the conflict, winning the 1945 Pulitzer Prize for Photography. Yet the photograph was repeatedly marred by claims that it was staged, something Rosenthal repeatedly denied. This likely extends from the fact the photograph depicts a second flag raising, when the original flag was replaced with a larger flag. This example gives a sense of the growing distrust surrounding photography, the medium no longer accepted as mere fact.

There was certainly reason to distrust the medium, given the range of techniques available to photographers to alter the impression and aesthetic of a photograph. A notable example is Yevgeny Khaldei’s (1917-97) photograph Raising a Flag over the Reichstagtaken in 1945. The photograph depicts the Soviet victory over the Nazis during the Battle of Berlin, symbolically shown in the raising of a Soviet flag on the Reichstag. The photograph was staged at Khaldei’s request, utilising soldiers available at the time to re-enact the action signalling the original capture. Staging was not the only munition available to documentary photographers in their aim to create powerful, resonant works. Before the advent of Photoshop, photographers were able to employ a range of editing techniques in the darkroom. Khaldei’s photograph was manipulated to add smoke to the scene, drawn from another negative, intensifying the drama of the image.

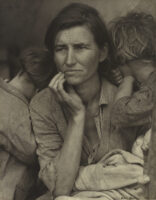

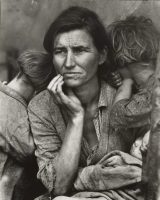

Other photographers used editing techniques to create more aesthetically appealing compositions to heighten the power of their works. In her famous photograph Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California, better known as Migrant Mother (1936), Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) removed the thumb of the woman depicted, Frances Owens Thompson (1903-83), that could be seen in the lower right side of the original photograph. This work is often held up as being the epitome of documentary photography, showing harsh, unflinching realism. Does the manipulation or removal of such details detract from the central message, and the ‘truth’, trying to be conveyed, or conversely, add to the power of the message and photograph? In her own words, Lange stated, ‘[a] documentary photograph is not a factual photograph per se… It is a photograph which carries the full meaning of the episode’. [33] The small lie is erased by the importance of the photograph to communicate a greater truth.

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother, 1936. Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program.

Dorothea Lange, Copy print of Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, 1936; Print by Arthur Rothstein, about 1960. Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program.

The communicative and propaganda potential of photography, and its capacity to be altered, is particularly evident in the photographs emerging from the early years of Joseph Stalin’s (1878-1953) rule in Russia and throughout the Cold War. When Stalin gained power in the 1920s, many photographs were taken of the leader, often depicting him with fellow Communist party members. Over time, these photographs were edited to align with shifting political and propaganda narratives within the party. Political opponents, removed through murder, were then removed from the photographic record. Nikolai Yezhov (1895-1940) who oversaw the Great Purge, regularly appeared in photographs with Stalin. In 1940, he was executed after falling from favour. Subsequently, all photographs depicting Yezhov were altered to remove his presence. This was a common practice, seen to enhance the support of Stalin and occurred on a public scale, but also within the personal sphere. Fearing retribution, individuals removed photographs of Stalin’s political opponents within their homes and personal effects, including images of their own family members. [34] Through removing and doctoring photographs, the intended effect was to rewrite historical, recorded truths, giving a sense of the power attributed to photography to alter opinion and represent history.

Related to this idea is the transformation a photograph undertakes when released or viewed by the public, sometimes taking on new identities, moulding into something apart from the initial vision of the photographer. The photograph’s context, placement and accompanying text, whether in a newspaper, online or in the museum, can all deeply influence the way in which the photograph is read and received. In 1951, Ruth Orkin (1921-85) took the photograph American Girl in Italy. The photograph shows a woman walking down a street whilst men call and beckon to her. The photograph intended to document the positive experience of a young woman travelling alone in Italy and was published in a Cosmopolitan article that encouraged ‘Don’t Be Afraid to Travel Alone’. The photograph was later adopted by some to illustrate the street harassment and dangers facing women, especially women travelling alone. However, both Orkin and the model, Ninalee Craig, then named Jinx Allen (1927-2018), stated the later interpretation does not reflect their positive experience of travel or intentions for the photograph. [35] This particular example indicates the way in which photographs can be adopted and appropriated to suit certain narratives, and the influence of outside forces on the way a photograph is read, perhaps diverging from the actual truth of the situation or the photographer’s concept and experience in creating the work.

Interpretation and Manipulation

The photographer’s subjective view should be considered in terms of how a photograph is framed and read, contradicting the idea that a photograph is an objective record. Henri Cartier Bresson (1908-2004) discussed capturing a moment that encapsulates a specific event, the famous ‘decisive moment’. A photograph shows precisely that, just one moment – the photographer has not captured the moment before, the moment after, what is happening above, below or to the side of the frame. As John Berger (1926-2017) noted, ‘Every image embodies a way of seeing. Even a photograph. For photographs are not, as if often assumed, a mechanical record.’ [36] The image created is framed by what the photographer perceives to be the most important or most aesthetically attractive moment. Frank Webster (b.1950) notes that photography needs to be viewed as a ‘selectionand interpretationof the world in two respects. First, from the point of view of the photographer who selects and interprets a scene of incident in the process of encoding an image. Second, from the perspective of a view who interprets (reads) the photograph in the process of decoding. This orientation views the photographic communication as an active process of interpretation, by both the creator and the viewer.’ [37]

There is a heightened concentration on the history and interpretation of the photographic medium in the mid-twentieth century, connected to the increased scholarship surrounding the medium. Many significant texts on the history of photography were published in the period, including Beaumont Newhall’s (1908-93) The history of photography from 1839 to the present day (1949) and Helmut (1913-95) and Alison (1911-69) Gernsheim’s The History of Photography from the Camera Obscura to the Beginning of the Modern Era (1969). These publications intended to represent the history of photography in its entirety. [38] These texts, however, neglect a vast history of photography through their narrow focus on Western white, male photographers. [39] Yet their influence remains. This may give reason to the dominance of predominately white, European, British and North American males in the history of the medium. The 1990s saw the expansion of historical scholarship surrounding photography, both with the museum and university context, paving the way for new histories and stories to emerge. In recent years, there has been a shift in thinking and practice as select scholars and curators look towards highlighting other narratives to provide a more representative and inclusive history of photography, giving a fuller, more accurate picture.

As scholarship on the history of photography expanded, so too did the possibilities of the photographic medium. In 1990, Adobe Photoshop was released. The programme was basic compared to contemporary standards, but the computer software enabled photographs to be easily and effectively manipulated through actions like cloning and removing sections of images, and adjusting the opaqueness, hue and saturation of photographs. [40] The software was relatively affordable and accessible, encouraging wider use. From this stage, arguably, photography could no longer be upheld as a truthful medium. This is despite the countless examples pre-Photoshop that prove the capacity for photographs to be manipulated, edited and adapted throughout the medium’s lifespan.

The apparent reality and honesty perceived to be inherent to the medium of photography meant that it could be readily manipulated in the service of implementing a supposed ‘truth’, whether for propaganda purposes, commercial gains, colonial ideologies or to prove something that seemed unproveable, from fairies to spirits. Possibly more ambiguous is the idea of photography’s ‘untruths’. If the camera captures more than the human eye, is this more truthful, or less? Does the practice of digitally colouring historical images enhance realism? Can an image be manipulated to convey a greater truth? These are more difficult to pin down and provoke reflection of what one considers to be a ‘truth’, and the role of photography in shaping truth-making.

Read part one of A Brief History of Photography and Truth

[1] Post-truth was the word of the year for 2016. It is defined as: ‘relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.’ ‘Word of the Year 2016’, Oxford Languages, https://languages.oup.com/word-of-the-year/2016/.

[2] Michael Zhang, ‘Fox News Ran Photoshopped Photos of Seattle Protests’, 15 June 2020, PetaPixel, https://petapixel.com/2020/06/15/fox-news-ran-photoshopped-photos-of-seattle-protests/.

[3] ‘Cloudy Sky, Mediterranean Sea’, Art Institute Chicago, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/126485/cloudy-sky-mediterranean-sea.

[4] See Thomas Ruff commission responding to Tripe’s photographic negatives ‘Tripe | Ruff by Thomas Ruff’, V&A, https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/tripe-ruff

[5] For further discussion on Fenton’s photographs see Susan Sontag, The Pain of Others (New York: Picador/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003).

[6] For further information see Ateya Khorakiwala, ‘Staging the Modern Ruin: Beaton’s “Sikander Bagh, Lucknow”’, Thresholds 41, Spring 2013, pp. 138-45.

[7] Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, ‘Photography,’ in The London Quarterly Review (April 1857).

[8] 1 in 4 deaths were from tuberculosis in the 19th century. Philippe Glaziou, Katherine Floyd, and Mario Raviglione,, ‘Trends in tuberculosis in the UK’, Thorax, 73:8 (August 2018), pp. 702–703.

[9] ‘Hippolyte Bayard’, The J. Paul Getty Museum, http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/artists/1840/hippolyte-bayard-french-1801-1887/

[10] See Catlin Langford, ‘Carte-de-visite’, Royal Collection Trust, https://albert.rct.uk/photographic-technologies/carte-de-viste

[11] Playful examples of cartes can be seen on the following website: ‘Trick Photography’, The Library of Nineteenth-Century Photography, http://www.19thcenturyphotos.com/?curcatID=161&nav=products

[12] ‘Public Faces: Photography as Social Media in the Nineteenth Century’, The International Centre of Photography, 27 August 2015, https://www.icp.org/perspective/public-faces-photography-as-social-media-in-the-19th-century.

[13] See Abigail Cain, ‘How Frederick Douglass Harnessed the Power of Portraiture to Reframe Blackness in America’, Artsy, 2 February 2017, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-frederick-douglass-photographed-american-19th-century.

[14] Geoffrey Batchen, ‘Dreams of ordinary life: Cartes-de-visite and the bourgeois imagination’, in Photography: Theoretical Snapshots, eds. J. J. Long, Andrea Noble and Edward Welch (London: Routledge, 2009), p. 91.

[15] For a further discussion on this aspect of photographic history, and more broadly the representation and use of photography by African Americans see Thomas Allen Harris, Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People, First Run Features, 2014.

[16] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that the link contains images of deceased persons. As an example of a carte, see the following photograph: http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1058958/photograph-unknown/. The individuals in this 1865 photograph have been identified as wearing kangaroo skin cloaks separate to their people’s culture. The photograph is from an album entitled ‘Views in the Australian Colonies: New Zealand and the South Sea Islands’, held in the Victoria and Albert Museum. The kangaroo cloak, or Buka cloak, was traditionally worn by the Noongar.

[17] Peter Quartermaine quoted in Derrick Price, ‘Surveyors and surveyed: Photography out and about’, in Photography: A Critical Introduction, ed. Liz Wells, London: Routledge, 2003), p. 83.

[18] Elizabeth Willis, ‘Overlooked and Forgotten: Representations of Aboriginal Pastoral Workers in Nineteenth-Century Victoria’, in Shifting Focus: Colonial Australian Photography 1850-1920, eds. Anne Mazwell and Josephine Croci (Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2015), pp. 46-57.

[19] Helen Ennis, Photography and Australia (London: Reaktion Books, 2007), p. 34.

[20] James Tylor, ‘Voyage of the Waka and, the Origin of the Dreaming’, https://www.jamestylor.com/voyage-of-the-waka.html; ‘Australian Artists Working with Photography – James Tylor’, University of New South Wales Art & Design, 11 December 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3KHFbl_siNY.

[21] Patrick Waterhouse quoted in ‘Restricted Images’, British Journal of Photography 7877 (November 2018), p. 53; ‘Restricted Images’, Patrick Waterhouse, https://patrickwaterhouse.com/archive/selected/restricted-images-made-with-the-warlpiri-of-central-australia/.

[22] ‘Spiritual Photography’, The Illustrated Photographer, 28 May 1869, 254.

[23] Dorothy Wilding, ‘In Pursuit of Perfection’, in Illuminations: Women Writing on Photography from the 1850s to the present, eds. Liz Heron and Val Williams (London: I.B.Tauris, 1996), p. 125.

[24] Wright and Griffiths are recorded as using a ‘Midg’ camera, similar to the Brownie box camera.

[25] Arthur Conan Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 1922, https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php/The_Coming_of_the_Fairies

[26] Despite this announcement, the cousins maintained they had seen fairies.

[27] Following WW1, there is a revival of spirit photography, particularly in Britain. Following the death of his son Kingsley in the war, Doyle commissioned spirit photographs with the hope of capturing an image of his son.

[28] Patricia Holland, ‘Introduction: History, Memory and the Family Album’ in Family Snaps: The Meaning of Domestic Photography, eds. Patricia Holland and Jo Spence (London: Birago Press, 1991), 1-14.

[29] See Catlin Langford, ‘Hand Colouring’, Royal Collection Trust, https://albert.rct.uk/photographic-technologies/hand-colouring.

[30] ‘Nature Copied in Colour: The Lates Developments of Photography’, The Graphic, 14 October 1911, p.16.

[31] See ‘History in Colour’, Reddit, https://www.reddit.com/r/ColorizedHistory/.

[32] Jessica Stewart, ‘History Comes to Life Through Beautiful Colorized Photographs’, My Modern Met, 9 November 2018, https://mymodernmet.com/retronaut-dynamichrome-colorized-photo-book/.

[33] Carrie Raymond, Women Photographers and Feminist Aesthetics (Abindgon: Routledge, 2017), p. 63.

[34] Erin Blakemore, ‘How Photos Became a Weapon in Stalin’s Great Purge’, History Stories, 8 April 2020, https://www.history.com/news/josef-stalin-great-purge-photo-retouching.

[35] John Allemang, ‘A snapshot of sexism of a portrait of composure’, The Globe and Mail, 12 August 2011, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/a-snapshot-of-sexism-or-a-portrait-of-composure/article590345/.

[36] John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: British Broadcasting Corporation/Penguin, 1972), 10.

[37] Frank Webster in quoted in Clive Scott, The Spoken Image: Photography and Language (London: Reaktion Books, 1999), p. 23.

[38] Kelley Wilder, ‘History of Photography’, Oxford Bibliographies, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199920105/obo-9780199920105-0041.xml#obo-9780199920105-0041-bibItem-0007.

[39] Their influence can be seen in latter texts. For instance John Szarkowski’s (1925-2007) lauded 1989 publication Photography Until Now only 16 of the 202 photographers represented were women.

[40] Harrison Weber, ‘This is what Adobe Photoshop looked like 25 years ago today’, Venture Beat, 18 February 2015, https://venturebeat.com/2015/02/18/this-is-what-adobe-photoshop-looked-like-25-years-ago-today-video/