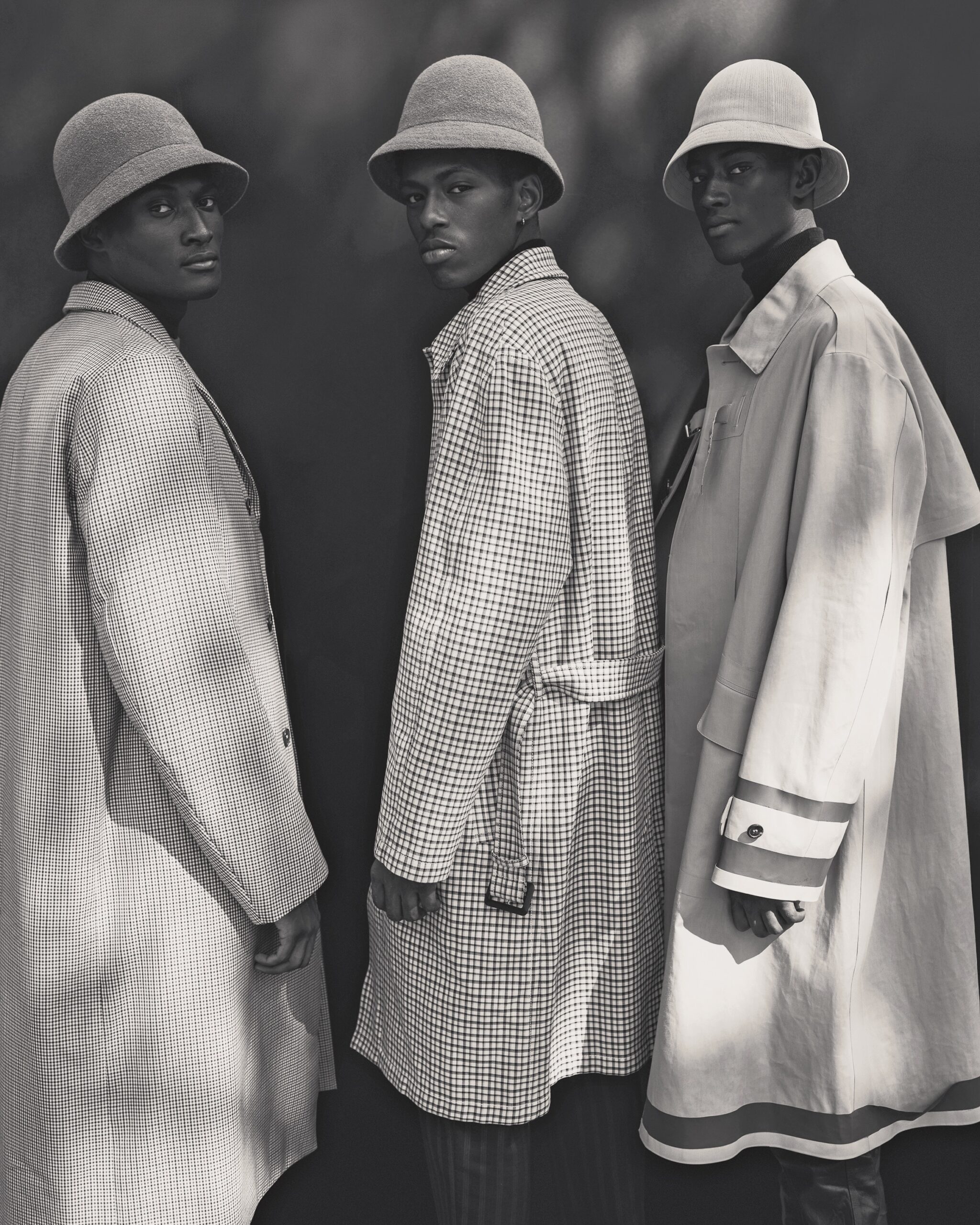

Image courtesy Stephen Tayo

The New Black Vanguard – Antwaun Sargent

6.7.20

In an exclusive excerpt from the Aperture publication 'The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion', Antwaun Sargent writes about the past, present and future of black representation in fashion photography. He discusses the role of the black body in the marketplace; the cross-pollination between art, fashion, and culture in constructing an image; and the institutional barriers that have historically been an impediment to black photographers participating more fully in the fashion (and art) industries.

“There is no question that represenatation is central to POWER. The real struggle is over the power to control IMAGES.” —Thelma Golden (1994) [1]

ICONS and ICONOCLASTS

In September 2018, American Vogue, one of the most influential magazines in fashion, published two covers of the global icon Beyoncé. It was her fourth appearance fronting Vogue, but these images became instantly renowned for their historic nature: her portraits were not captured by Mario Testino or Patrick Demarchelier, as they had been in the past, but by the young black image maker Tyler Mitchell. At just twenty-three years old, Mitchell became, remarkably, the first African American photographer hired to shoot the cover of the venerable publication.

The fashion image is a totem. Over the last century, photographers have taken commanding pictures of models, celebrities, and people cast from daily life. These images have supplied the main-stream consciousness with both positive and negative representations of beauty and the body, exerting influence on our collective tastes and understandings of identity. Fashion photographs exist in various incarnations and often mix different genres in a single image, shifting as quickly as the looks, trends, and subjects they document. Fashion pictures are images that showcase style; viewed critically, they offer a means of cultural reflection, tracking changes in societal attitudes, politics, sexuality, social and economic structures, and the value that we ascribe to expressions of individuality. Technology – namely, digital and social media – has changed what we consider to be and how we consume fashion images. We now seemingly encounter them everywhere we look; however, in our image-obsessed culture, the cover of a fashion magazine is still regarded as one of the biggest platforms on which fashion photographers can make a statement.

With his groundbreaking Vogue shoot Mitchell became a member of a small club of black image makers who have contributed photographs to the magazine’s pages over the last century; this group includes Awol Erizku, Lorna Simpson, and Gordon Parks, who began working as a Vogue staff photographer in the mid-1940s. Parks, who is well known for his black-and-white images of postwar African American life, notably shot beautiful and elegant pictures of white models, such as Veruschka. At the time (the 1960s), black models and photographers, because of their race, were considered “‘unsuitable’ for publication in mass-market fashion titles.”[1] The black fashion model and author Barbara Summers noted that black beauty has long been a contested notion in popular culture: “Beauty is a power. And the struggle to have the entire range of black beauty recognized and respected is a serious one”[2] – a struggle that has relied, in part, on the camera to envision it and the magazine to publicize and normalize it.

Discrimination has excluded from widespread publication black photographers such as James Van Der Zee, who created some of the most alluring fashion images of early twentieth-century black life, and Anthony Barboza, an early member of the influential black photography collective Kamoinge, to name just two. Barboza, a prolific image maker who trained with noted black jazz and fashion photographer Hugh Bell in the early 1960s, was the first photographer to shoot the supermodel Iman in the 1970s. Recently, he observed that even as progress has slowly opened the doors for some black photographers to shoot certain stories, these artists were not being allowed to share their visions on the covers. In an Instagram post, published a few days before Mitchell’s Vogue cover, under an image of a ten-page spread entitled “A Black Woman’s Beauty,” which Barboza photographed for Vogue’s now defunct Beauty Book magazine in the 1980s, he wrote: “As a #BlackPhotographer with a history of photographing black people in Fashion I was never considered for shooting a cover of #Vogue magazine then or even now apparently.”[3]

Over the last few decades, the same stable of photographers, usually white and male, with the exception of Annie Leibovitz,[4] have shot the majority of covers and fashion stories of major magazines, exerting an outsized influence on how identity is styled in the popular photographic image. Fashion images are aspirational: people feel affirmed or alienated by the likenesses that stare back at them. For those who have not met the narrowly defined notions of gender, class, and beauty seen in the images, it can feel like a personal failure; a feeling of dislocation and invisibility have often met these viewers, subtly communicating that their bodies, hair, and skin were not desirous.

Mitchell’s images of Beyoncé signaled the power of change within the legacy of the periodical. A year prior, Awol Erizku shot a series of highly stylized images of the singer that celebrated black maternality, which were directly uploaded to her website and to Instagram, cutting out traditional gatekeepers. Yet the Vogue cover shoot with Mitchell seemed to resonate more given its message that black photographers’ images should regularly be given pride of place on the covers of fashion publications like Vogue. The two covers are striking for their intimacy and vulnerability and for how they use the clothes to make a statement about woman-hood and cultural solidarity. One cover depicts Beyoncé gazing directly into Mitchell’s lens. Drenched in natural light, she poses in an ivory Gucci dress against a matching white sheet used as a backdrop, and she wears a flower headdress — a nod to that season’s runway trends. The other cover, packed with symbolism, arguably signals the historic nature of the shoot: the star stands against a lush forest and holds a white sheet that billows over her head. She wears a tiered Alexander McQueen dress featuring the red/green/black tricolor that alludes to black nationalistic pride and power. It is a statement that is heightened by her hair, braided into cornrows. The image isn’t a traditional fashion picture.[5] And that was the point for Mitchell, for the magazine’s editor Anna Wintour, and for Beyoncé herself, who keenly wrote in the pages that followed: “If people in powerful positions continue to hire and cast only people who look like them, they will never have a greater understanding of experiences different from their own. They will curate the same art over and over again, and we will all lose.”

Both the cover images and the inside spread were radical for their mundanity and quiet self-composure, which are meant to show the ordinariness of black existence and excellence as it might exist in what Mitchell calls “black utopic space.” He explains:

“I realized what I am visually conveying is black beauty. How that can be made regular, a part of daily life rather than something that’s visualized as special or eccentric, or different, how do you normalize that, with-out being exoticized, it’s just vernacular, everyday beauty… Through the photos and the videos, there’s kind of a sense of play, innocence, and freedom to all of it. Whether it’s the striking element of some-one’s gaze, when I do a fashion shoot, or, like, in my portraits of Beyoncé, which have a certain intimacy you’ve never really seen her viewed as, or viewed under… the basis of my education has been good images, of people in the universe. It’s never been pushing this agenda of great fashion images, à la [Irving] Penn, [Steven] Meisel, or [Richard] Avedon. It’s always been about the person in the picture and my relation- ship to the person, which gives the images a social undertone… As a fashion photographer, I’m thinking of conveying black beauty as an act of justice.”[6]

NEW GAZES

Mitchell’s historic Vogue shoot also speaks to a recent shift in who gets to take fashion images and what is represented in them. The pictures and their makers are a part of a new black vanguard of photographers, who are working internationally, across the African diaspora, and using their cameras to create contemporary portrayals of black life that are reframing established representational paradigms. The loose collective, which includes, along with Erizku and Mitchell, Campbell Addy, Arielle Bobb-Willis, Micaiah Carter, Nadine Ijewere, Quil Lemons, Namsa Leuba, Renell Medrano, Jamal Nxedlana, Daniel Obasi, Ruth Ossai, Adrienne Raquel, Dana Scruggs, and Stephen Tayo, among others, are making fashion images that establish the significance of the black figure — and even more radically, the black creator – as a new ideal in contemporary culture. Their images blur the conventional boundaries between art and fashion photography. Their photographs of black models – whether professional models or those cast from the photographers’ families, the street, or Instagram – and celebrities draw on such genres as portraiture and documentary, conceptual, and still life photography, bringing in a whole new set of references and black aesthetics as a way to introduce innovative possibilities for the fashion image.

The New Black Vanguard’s photography is rethinking how the fashion image can be less censorious and more reflective of real life. These images not only perform the traditional service of selling fantasies to attract customers, but also explore race, gender, and desire in new and productive ways, resulting in a reimagining of what constitutes a fashion image, widening the scope of representation and broadening the definitions of fantasy and power that are rooted in specific cultural contexts. In an interview for Aperture, the queer photographer and artist Collier Schorr speaks about the power of fantasy and intimacy in the fashion image, asking if intimacy can be “a kind of gaze of empowerment, inclusion, and warmth.” Thinking of looking at fashion pictures as a young person, she notes, “I could be repulsed by fashion images. I could be hurt by fashion images. And, I could be scarred by fashion images. I wanted to replace the pictures I found alienating with my pictures, so that I would somehow create a healthier pictorial environment for kids.”[7]

Something similar is at work with the New Black Vanguard. The narratives their work generate are wholly new visions of the glamorous black figure, realized through their eyes with a beauty and diversity that allows their models to tell many different stories through fashion. Their images consider the construction and deconstruction of the body as it relates to identity through dress; they also address what it means to depict bodies, in fashion, that have once been invisible in the industry. These black-produced images carve out space for black beauty, a long-contested notion in the mainstream that is known fact before the lens of a black photographer. The images also serve to complicate and contradict conventional notions of beauty by presenting fluid and intersectional identities. Photographer Campbell Addy’s personal exploration of his homosexuality and spirituality in the series Matthew 7:7&8 (2017) is one such example. In turning the camera onto themselves and their communities by using models cast to represent their distinct realities, or through the use of self- portraiture, these image makers’ own subjectivities are being seen within their images. This fresh way of thinking has resulted in realistic images of the black body in fashion images that had previously imposed imagined, and often harmful, notions onto it.

The new movement also sees black women photographers – such as Rhea Dillon, Delphine Diallo, and Dana Scruggs, among others – sharing their visions of what constitutes style. These images speak to the ways women want their concerns and bodies to be represented in an industry that has showcased very few female perspectives. “As a girl, I never identified with anyone in the pages of magazines,” the photographer Nadine Ijewere has explained. “Now, we’re sending a message that everyone is welcome in fashion. There are so many different types of beauty in the world. Let’s celebrate them all!”[8] In 2016, Ijewere, who in 2018 became the first black woman to shoot a cover for any of Vogue’s editions,[9] created the studio portrait series The Misrepresentation of Representation. For this body of work, women of color, in an array of culturally specific headdresses, challenge the construction of the “other,” exposing “the whole concept of orientalism and representation [as] a staged concept created by the Western world during colonialism,”[10] which has been a recurring trope in fashion photography since the 1950s. Adrienne Raquel, another emerging female voice, has used what she calls a “female gaze” to construct color-filled fantasies in which women “possess an intricate, yet undeniable level of power, beauty, pureness, and sensuality.”[11] In their images women often embody characteristics and clothing that present them as something other than just sexy objects of male desire.

![Image: Arielle Bobb-Willis, [New

Orleans], 2017; from [The New Black Vanguard (Aperture 2019)], © the artist](https://photo.org.au/api/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/NBV_013_Bobb-Willis_837-167x200.jpg)

Arielle Bobb-Willis, New Orleans, 2017; from The New Black Vanguard (Aperture 2019), © the artist

The African American photographer Arielle Bobb-Willis has described her images as antirepresentational in how they elude desire. Her photographs – such as San Francisco(2017), in which a black male stands on a sandy seaside dune, in a red shirt and blue pants, his head tilted down – often conceal the faces of her subjects, who are swathed in brilliant monochromatic garments. Inspired by the modernist painter Jacob Lawrence’s expressive cubist style, these images show figures who are contorted into positions that render them anonymous and that eschew the traditional poses of portraiture.[12] There’s a rejection of the overrepresentation that the black body has experienced, an evasion of what representation has meant in practice – swapping out one exceptional black body for another. The images are less about what the black body may look like but what it experiences emotionally.

CHANNELING HISTORY

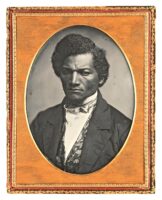

In their fashion image making, the New Black Vanguard is influenced, in part, by the titans and contemporary players in the fashion industry, such as Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, and Mario Sorrenti. But because people of color were routinely ignored or exoticized in mainstream fashion press, what is striking about the New Black Vanguard is the way their images are influenced by the history of black portraiture, which spans the art, vernacular, documentary, and studio photography genres as well as contemporary painting. In black portraiture the style picture has long been a tool of identity expression; an intervention in the area of representation; a way of “fighting photography with photography,” as the black photographer Ayana V. Jackson has noted.[14] To create what Micaiah Carter calls “a new perspective,”[15] their pictures sometimes reference past debates about producing “positive images” that arose in the black nationalist movements of the 1960s; their photographs also address philosophies of liberation that date back to the abolitionist and most photographed man of the nineteenth century, Frederick Douglass. He pioneered the use of the image to capture his sharp sense of style and gravitas in daguerreotypes and ambrotypes, such as Samuel J. Miller’s black-and-white portrait Frederick Douglass (1847–52).[16]

Samuel J. Miller, Frederick Douglass, 1847–52 Courtesy and © The Art Institute of Chicago

Douglass’s conscious use of the camera as a tool of self-invention is a concept that became a central part of black image making, as the role of photography in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century evolved from simple documentation of a person or an event to the construction and creation of an image. Black photographers who followed, such as Thomas E. Askew, Cornelius M. Battey, and James Van Der Zee, created images of the self-fashioned black subject reimagined. “I wanted to make the camera take what I thought should be there, too,” Van Der Zee once noted.[17] In Eve’s Daughter (ca. 1920), for example, an African American woman “embodies a joyful, Edenic figure, standing in front of a studio backdrop that pictures an idyllic lake and trees. She wears a sheer wrap, with a wreath of leaves crowning her dark, upswept hair and sprigs of white flowers lying by her bare feet. To heighten the sense of natural drama, Van Der Zee hand-etched marks onto the negative that detail the leaves and flowers, and that suggest a pair of swans in the water.”[18]

More recently, in an effort “to create images that compel [black] stories and cultures and ‘stereo-types,’ and create moods and environments that are almost unworldly within the context of blackness,”[19] the New Black Vanguard has not only referenced image making in the black American context but also pulled from African diasporic photo histories. Photographers such as Kwame Brathwaite, Coreen Simpson, and Jamel Shabazz have documented black women, men, and children in a given era’s popular fashions and looks, which ranged from the natural hairstyles popular during the Black Power and Black Is Beautiful movements of the 1960s and 1970s to the hip-hop–inspired street style of the 1980s and 1990s. In that latter era, unsuspecting and stylish strangers donned fur coats; tailored and outsized suits; baggy, sagging pants; and the bootleg, high-fashion-inspired garbs that emerged from Dapper Dan’s Harlem atelier. All of these looks were expressions of freedom that bucked European trends and spoke to the pride that the subjects took in their racial identity.

These styles, catalogued by black image makers, now serve as an informal archive for New Black Vanguard photographers and have been appropriated by major brands such as Gucci, which in 2017 ran a campaign, entitled “Soul Scene,” featuring a cast of black models in late 1960s-inspired fashions; it was shot by the white photographer Glen Luchford, who claimed to have been inspired, in part, by the carefree black-and-white studio and night life images of the Malian photographer Malick Sidibé. The campaign marked the first time that the brand had hired a cast of black models, and critics, such as the playwright R. Eric Thomas, denounced it for its surface appeal. In the New York Times Thomas wrote that “while the campaign purports to celebrate black soul, it smacks of performance rather than genuine homage. Is it offensive? Not really. Is it appropriation? Well, there’s the rub. It would be if the ads included the culture. Instead, Gucci presents a reverent, painstakingly-recreated facsimile of a culture. More than anything, the campaign is about the look. It’s just drag. This is soul as drag.”[20]

Image courtesy Stephen Tayo

Ruth Ossai, Nadine Ijewere, and Stephen Tayo have more convincingly sourced inspiration from the mise-en-scène studio portraiture and street scenes of photographers – including Sidibé, Samuel Fosso, James Barnor, and Seydou Keïta – who, working in Africa in the late 1950s through the 1970s, captured the youthful energy, fashion, and vivid forms of self-styling as postcolonial independence movements swept the continent. Barnor, a photojournalist in Accra, Ghana, moved to London in 1959, where he shot covers for Drum magazine; his 1960s color fashion work, made in the UK, bears a striking similarity to the “Black Is Beautiful” photographs of the same era by Kwame Brathwaite in Harlem. Sidibé and Keïta, whose early work was exhibited widely in the 1990s following the first Rencontres de Photographie in Bamako, Mali, were both commissioned by fashion titles and international magazines, including the New York Times Magazine and Harper’s Bazaar. Fosso, famous for his elaborate self-portraits, has worked largely within the art world, but he accepted a fashion commission by Vogue Hommes International in the late 1990s, when the magazine was edited by Phil Bicker and distinguished by fashion photography from emerging stars, including Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Koto Bolofo, Youssef Nabil, and Hannah Starkey.[21]

Malick Sidibé for New York Times Magazine, “Prints and the Revolution,” April 2009.

The New Black Vanguard has looked to these forerunners to explore their own roots and to portray their communities and families both in Africa and in the West. By continuing the legacies of these earlier photographers and drawing from more recent ideas from the 1990s, when artist Renee Cox explored Afrofuturism and feminist theorist bell hooks called for black images that contained an “oppositional gaze,” the emerging class of black fashion photographers are inserting their own fantastic narratives into the contemporary as a way to show those values that they consider culturally significant. These images elude and contest a history of fashion that has relied on blackface, cultural appropriation, and racist tropes that still, every few seasons, pop up in fashion magazines, advertisements, and the clothing seen on runways. In an industry that increasingly celebrates itself for improving its outward diversity —that is, in campaigns, runway presentations, and magazines — such tone-deaf missteps could be avoided if the industry’s gatekeepers of editors, fashion designers, and fashion label directors, as well as the people behind the scenes in production, were themselves a more diverse group.

A source of inspiration for photographers Arielle Bobb-Willis and Awol Erizku lies in the canonic history of representation and erasure found in contemporary and historical painting. Erizku, who once declared that his goal was to make black-ness as universal a symbol as whiteness, draws on Old Masters to create images that are a part of a visual lineage that includes modern black stars, such as Kehinde Wiley, Barkley L. Hendricks, and Mickalene Thomas. In pose and appearance their stylish sitters – all of whom are painted from photographs – examine and challenge the black body’s general absence from and relationship to popular culture as well as the Western art canon’s fantastical, exoticized notions of that body. Erizku’s commercial images of celebrities such as Beyoncé, Viola Davis, and Lauren London and of the late rapper Nipsey Hussle are rooted in an art practice that explores the power and beauty of the black figure.

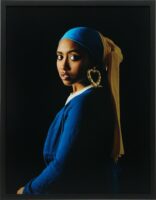

In 2009, Erizku made The Girl with the Bamboo Earrings. The portrait recasts Vermeer’s subject in Girl with a Pearl Earring – and draws on Norman Lewis’s modernist work Girl with Yellow Hat (1936) – as a beautiful black girl whom Erizku knew growing up in the Bronx; she used various accessories – earrings, barrettes and beads, Jordans, gold- and silver-plated name necklaces – to display worth, care, and status. The use of style as a device in the work of Erizku and that of his peers “not only illustrates the state of being sharp,” as historian Richard J. Powell argues, but “epitomizes something fundamentally artistic in the way the people depicted present themselves to the world at large. This art of self-representation is far more intangible and multivalenced than mere style for style’s sake.”[22]

Awol Erizku, Girl with a Bamboo Earring, 2009. Courtesy the artist.

These new black voices are creating “a proper counterargument to current conventions of fashion photography,” as curator Charlotte Cotton wrote of the innovations first seen in the 1990s from image makers Steven Meisel, Peter Lindbergh, and Inez & Vinoodh, who have since become the dominant editorial presence. The 1990s, as Cotton notes, was “a time of big hair, skirt suits, white shirts, and supermodels dressed in Azzedine Alaïa.”[23] Today, in formulating their own “counterargument,” members of the New Black Vanguard are making fashion images that focus on an array of attitudes, depictions, and poses and that reimagine notions of beauty, style, and the status of the black figure for their generation. In borrowing from and breaking with the canons of traditional black portraiture and fashion photography, the emerging new talent is creating new, self-referential visions of black power that continue the work of normalizing the representations of blackness by diversifying the images that record its myriad forms. Their alluring – and affecting – deliberate constructions counter a history of misrepresentation in the very magazine pages that once upheld myths of black social and cultural inferiority. For the New Black Vanguard, experimentation with the medium has resulted in capturing what postwar documentary photographer Roy DeCarava once described as “the kind of penetrating insight and understanding” of black people that only a black photographer can interpret. Like DeCarava, these artists believe that who makes the image is as important as the image itself and that black people should be portrayed “in a serious and in an artistic way.” [24]

These disruptive, fresh images have emerged at a time when several black individuals are being recognized for bringing their perspectives to fashion: makeup artist Pat McGrath, designer Kerby Jean-Raymond of Pyer Moss, stylist Ib Kamara, hairstylist Nikki Nelms, and magazine editor Edward Enninful. Established black art photographers such as Hassan Hajjaj, Carrie Mae Weems, Mickalene Thomas, and Deana Lawson are also bringing their concerns to the covers and pages of magazines. Lawson’s Garage magazine cover shoot of Rihanna breaks from what we have come to expect to see of the pop star. She reclines on a couch, her long gold nails framing her beautiful face. In a blue Y/Project cape and crimson bodysuit she is the picture of a modern Venus. A small portrait of the singer, taken when she was no more than ten years old, rests against a purple backdrop and contrasts with her public status as a contemporary icon. It is typical of those images taken in elementary school on picture day and stored inside a family photo album as a keepsake or prominently displayed in a makeshift gallery that lines the wall of a parent’s home. Lawson, who rarely takes fashion assignments, is known for working like a painter in her methodical construction of images and her exquisite attention to detail and symbolism. Her collaboration with Rihanna, therefore, is an exemplary moment of photography between art and fashion. Her work with Rihanna remakes the fashion image into a double portrait that connects the singer and fashion entrepreneur’s private girl- hood dreams to the self-assured and successful woman we see before us. It suggests that the fashion image is also an opportunity to go deeper than surface reflections; it is an occasion to display inner beauty.

![Image: Dana Scruggs, [Fire on the

Beach], 2019; from [The New Black Vanguard (Aperture 2019)], © the artist.](https://photo.org.au/api/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Scruggs_ZR_SHOT_01_500_30x40print-200x150.jpg)

Dana Scruggs, Fire on the Beach, 2019; from The New Black Vanguard (Aperture 2019), © the artist.

The New Black Vanguard exhibition is on display at Bunjil Place until 27 September 2020 – part of PHOTO 2021’s expanded program.

ENDNOTES

[1] Thelma Golden, “My Brother,” from Black Male: Representations of Black Masculinity in Contemporary American Art(New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1994).

[2] Vogue ran its first “fashion portrait” of Gertrude Vanderbilt, taken by Adolph de Meyer, Vogue’sfirst staff photographer, in 1913. Magdelene Keaney, Fashion Photography Next(London: Thames & Hudson, 2014), p. 7.

[3] Barbara Summers, Skin Deep: Inside the World of Black Fashion Models(New York: Amistad, 1988), preface.

[4] Anthony Barboza (@anthony_ barboza_photographer), August, 4, 2018, caption, https://www.instagram.com/p/BmEERG5BykX/.

[5] Annie Leibovitz notably shot the historic 2009 Michelle Obama Vogue cover. Given the Obamas’ keen interest in statecraft, sartorial politics—wearing designers of color, for example—and black artists and image makers, it stands to reason that if that image were made today, it would have been a black photographer behind the lens. Beyoncé’s inspired but shrewd decision to collaborate with Mitchell was an investment in his future, and the future of black portraiture, not unlike Michelle Obama’s choice of Amy Sherald for her official portrait where she is seen in a halter gown covered in geometric shapes, made by the label Milly. The patterns, for Sherald, allude to the work of the Gee’s Bend Quiltmakers, an African American collective of women based in Alabama.

[6] The fashion critic Robin Givhan took issue with the images, arguing traditional fashion images are “glossy” and “iconic.” Robin Givhan, “Beyoncé’s VogueCover Is Historic But Not Iconic,” Washington Post, August 6, 2018, https://www.washington post.com/news/arts-and entertainment/wp/2018/08/06/beyonces-vogue-cover- is-historic-but-not-iconic/.

[7] Tyler Mitchell, in an interview with Antwaun Sargent, “Tyler Mitchell: To Convey Black Beauty Is an Act of Justice,” WePresents, March, 6, 2019, https://wepre sent.wetransfer.com/story/tyler-mitchell/.

[8] Matthew Higgs and Collier Schorr, “Collier Schorr: Humanity, Visibility, Power,” Aperture, issue 228, “Elements of Style,” fall 2017, pp. 24–35.

[9] Hayley Maitland, “26-Year-Old Photographer Nadine Ijewere on Her Historic VogueCover,” British Vogue, December 12, 2018, https://www.vogue. co.uk/article/nadine-ijewere-interview.

[10] On the occasion of the December 2018 “Future Issue,” Edward Enninful, the first black person to become an editor of a Voguetitle, wrote of the historic cover, “Whether it is fashion photography’s bright young thing Tyler Mitchell or Nadine Ijewere—who, with her portrait of global superstar Dua Lipa (herself a remarkable game changer) has become the first black woman ever to shoot a Vogue cover—a common theme to their work surely has to be integrity. They are all so honest. I don’t get the feeling they are doing it for fame. They do it for art and the times they live in, not just so they can book a Prada campaign. They have a mission and care deeply about changing the world we live in.” https://www.vogue.co.uk/article/dua-lipa-january-cover-future- issue-british-vogue-2019.

[11] Katherine Brooks, “One Woman Is Challenging the Stereotypes That Plague Fashion Photography,” Huff Post, March 17, 2016, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/nadine-ijewere-representation-photos_n_56d72064e4b03260bf78dcfc.

[12] In a conversation with the artist in April 2019, Raquel discussed the motivations behind her photography practice.

[13] Antwaun Sargent, “A Young Photographer Finds Inspiration in Jacob Lawrence, Fashion Photography, and Her Own Struggle with Depression,” New Yorker, December 9, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/a-young-photographer-finds-inspiration-in-jacob-lawrence-fashion-photography-and-her-own-struggle-with-depression.

[14] Antwaun Sargent, “With a New Art Fair and Museum, Marrakech Presents African Art on Its Own Terms,” Artsy, February 28, 2018, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-new-art-fair-museum-marrakech-presents-african-art-terms.

[15] Antwaun Sargent, “A 21-Year-Old Photographer Brings ’70s Black Power to Modern Times,”Vice, June 1, 2017, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/mbqm9p/micaiah-carter-photographer-black-power- modern-times.

[16] Deborah Willis, Out [o] Fashion Photography: Embracing Beauty (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), p. 17.

[17] Margo Jefferson, “Harlem’s Face on Its Own Terms,” New York Times, October 20, 1993, https://www.nytimes.com/1993/10/20/books/books-of-the-times-harlem-s-face-on-its-own-terms.html.

[18] Alina Cohen, “The Photographer Who Captured the Glamour of the Harlem Renaissance,” Artsy, March 27, 2019, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-photographer-captured-glamour-harlem-renaissance.

[19] Ibid.

[20] R. Eric Thomas, “Gucci’s Diversity Drag,” New York Times, April 17, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/17/fashion/ gucci-black-models-diversity.html.

[21] Adam Murray, “The International Style,” Aperture, issue 228, “Elements of Style,” fall 2017, pp. 94–99.

[22] Richard J. Powell, Cutting a Figure: Fashioning Black Portraiture(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), p. 4.

[23] Charlotte Cotton, “State of Fashion,” Aperture, issue 216, “Fashion,” fall 2014, pp. 45–52.

[24] Randy Kennedy, “Roy DeCarava, Harlem Insider Who Photographed Ordinary Life, Dies at 89,” New York Times, October 28, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/29/arts/29decarava.html.