Image: Sara Oscar

Q&A with Sara Oscar

5.3.21

Sydney-based artist Sara Oscar shares some insights into the inspiration behind—and process of making—her PHOTO 2021 commission, Most Wanted.

Hello Sara, please start by telling us something about yourself that is not in your bio.

My origin story is rather ordinary. On weekends as a child I spent a lot of time with my grandfather who was obsessed with photography. He would regularly bring out his collection of old cameras—a 1930s Leica, a 1940s Rolleiflex, a Box Brownie. We took photographs, I loved the magic of seeing the world in reverse through a ground glass. We also looked at photographs together. He had an extensive collection of images he had taken in India, extraordinary pictures from the time between British colonisation and Indian Independence; the rise of cinema, military presence, protest, train travel, natural disaster, landscapes, family life. He brought his collection of photographs with him when he migrated to Australia, it was his memory box. There were thousands of photographs, and I would sort through them over and over again, discovering new things about my family’s life. The appeal for me was being able to make stories and connections between images, a bit like detective work – there are an infinite number of stories that you can tell about all of the different details that present themselves to you. Going through that collection, and taking photographs really informed the type of work that I make now, especially my fascination for archives.

Image: Sara Oscar, Grandfather’s archive, c. 1932, Afghanistan

What are you exhibiting at PHOTO 2021?

I am showing a new work called Most Wanted. The work is a sequence of portraits of various subjects of various ages that draws on the posing conventions of police profile photographs and passport photographs. These conventions are a universally recognisable way of standardising and regulating the human body without expression, subjectivity. In the series, the subjects are photographed in two ways, in profile, or looking directly at the camera. Some of the subjects face one another, have their backs to each other, and others look directly at the camera—they are in a way, lined up. In this work, I’m interested in the tension that can build up between images in a sequence, by what is suggested in the work when these conventions are followed. These conventions are so recognisable to us that they don’t require any explanation, their meanings are overly determined by these conventions. I’m interested in working with that excess of meaning.

What inspired this project?

Andy Warhol’s paste up work, Thirteen Most Wanted Men from 1964, where he created a large-scale mural of appropriated photographs of 13 most wanted criminals from New York’s police departments. The men are good-looking so I guess he was playing around with masculine ‘desire’. I wanted to know how a work like this would translate sixty years later in a post-truth age, and what it would mean for a woman to work with a similar premise, but to move the work away from its inherent focus on the masculine subject.

![13-Most-Wanted-Men-1964 Image: Andy Warhol, [13 Most Wanted Men], 1964](https://photo.org.au/api/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/13-Most-Wanted-Men-1964-188x200.jpg)

Image: Andy Warhol, 13 Most Wanted Men, 1964

How does it relate to the theme for PHOTO 2021: ‘The Truth’?

I don’t think photography has much to do with truth, even though the medium tends to be associated with terms like evidence and proof. Context and conventions help determine what we believe to be true. My work, Most Wanted shows how truths are wholly reliant upon conventions in ways of seeing, shaping, ordering and ‘knowing’ the world, and these conventions help us establish something as plausible and therefore true. My work suggests that we shouldn’t confuse photographic realism with truth.

Can you tell us about the process of making this work?

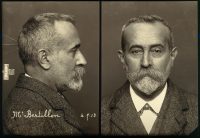

I started by looking at the serial nature of institutional photographs, particularly the typological systems created by Francis Galton (the father of eugenics) in the 1890s and Alphonse Bertillon in the early 1900s. Both created vast archives of criminal bodies, these photographs were on a compositional level, standardised and designed to be considered in collections. These conventions have not changed much since the 1890s. These archives build institutional ‘knowledge’ of particular types of humans, from the ‘suspicious’ looking person to the suspect more likely to behave in a particular way based on their physical features.

In making this work, I drew on the conventions of this ‘ethnographic’ style of portraiture along with the idea of the police identification photograph: a side photograph and a frontal photograph. I used this as a starting point to take the portraits and to order the sequence of images in a row based on visual resemblance – it is a system of ordering that is fallible and human. This is a long way from the ordering system used by the algorithmic logic of facial recognition software to identify subjects by governments and institutions. In my series, the subjects turn to face one another rather than lining up in a row to be identified, some subjects look alike, others might be wearing similar items of clothing. In some photographs, the faces are cropped, in others, the ‘side photograph’ edges towards the look of a fashion photograph – the meaning of the work gets obfuscated by the way conventions drift to different ‘genres’ of photography: from mug shot, to social media profile photograph, to fashion image, to headshot.

The sequencing in my work is really important because there is a pull to think about the images together and make connections, it is like putting positive and negative sides of a magnet together – you can’t help but want to bring them together and make stories about why these subjects have been brought together. That is perhaps the confusion between the epistemological value of a photograph and its power of suggestion.

![Galton Image: Francis Galton, from [Inquiries into Human Faculty and its Development], 1883](https://photo.org.au/api/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Galton-120x200.png)

Image: Francis Galton, from Inquiries into Human Faculty and its Development, 1883

Image: Alphonse Bertillon. Photograph, 1913

What do you hope audiences take from your work?

I have chosen a convention of representation that is already extremely loaded. I hope that the excess of meaning in the work draws attention to the importance of convention in the ways we read images and, look at images of bodies.

If your work at PHOTO 2021 was a song, what would it be?

Well, photographs show rather than speak so I don’t know if I could really place a song to the series. Perhaps it would be ‘Hurricane’ by Bob Dylan. The song is about a boxer Rubin Carter, who was wrongfully convicted of a crime he didn’t commit.

Which other artists or exhibitions are you looking forward to seeing at PHOTO 2021?

Joan Fontcuberta, Cristina de Middel, Zanele Muholi and so many others

And finally, what advice would you give to your 15 year old self?

It’s okay to be wilful.

Additional image credits:

Credit for image of Francis Galton

Credit for image of Alphonse Bertillon: Wellcome Collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)